Medical issues can happen to anyone, from a rancher checking his fence line, to a hunter in a tree stand, to a cop patrolling a beat. Rural or metropolitan doesn’t matter.

Medical emergencies occur more than gunfights simply because there are so many different ways for casualties to occur. Consequently, a situation requiring immediate medical attention should be looked at as a when, not an if. I have admittedly neglected this aspect of training. Sure, I’ve had rudimentary first-aid training, but nothing that would make me capable of dealing with traumatic injury.

Table of Contents

LONE STAR MEDICS AND CAREFLITE

Medic-1 is a class put on by Lone Star Medics in partnership with CareFlite. It focuses on traumatic injuries of various types, including puncture wounds, crush injuries, broken bones, and burns, and how to treat them. What sets this class apart is that students also learn how to choose and clear a landing zone to CareFlite specifications and use hand signals to help in landing a CareFlite helicopter.

Because I often find myself away from major population centers, knowing not only how to apply first aid but also how to bring in follow-on responders is crucial. First aid doesn’t end when somebody proclaims the ambulance or helicopter is on the way. One must be able to bring them in and get them out as safely and quickly as possible.

Lone Star Medics was created in 2009 to provide field and tactical medical instruction to military, police, fire, EMS, and prepared citizens. Caleb Causey, owner and lead instructor at Lone Star Medics, is a former U.S. Army medic. Assisting Caleb for this course were Kyle Omberg and Jim Richardson. Kyle and Jim are both public safety gurus, serving in law enforcement, fire service, and EMS.

CareFlite is a 501 C3 non-profit company whose goal is to provide ambulance services for the five Class 1 trauma centers in the Dallas/Fort Worth (DFW) metroplex. CareFlite can respond with ground, rotary-wing and fixed-wing ambulance service over this sprawling area. In DFW, CareFlite is known for their rotary-wing ambulance service using Bell 222s and Augusta A109Es.

Representing CareFlite on the ground for this course was David Dunson. David has been a paramedic for 20 years, the last ten on CareFlite’s helicopters as a Flight Paramedic. Our CareFlite team in the air consisted of Pilot Jerry Porter, Flight Nurse Shaun Michael Scott, and Flight Medic James Bailey.

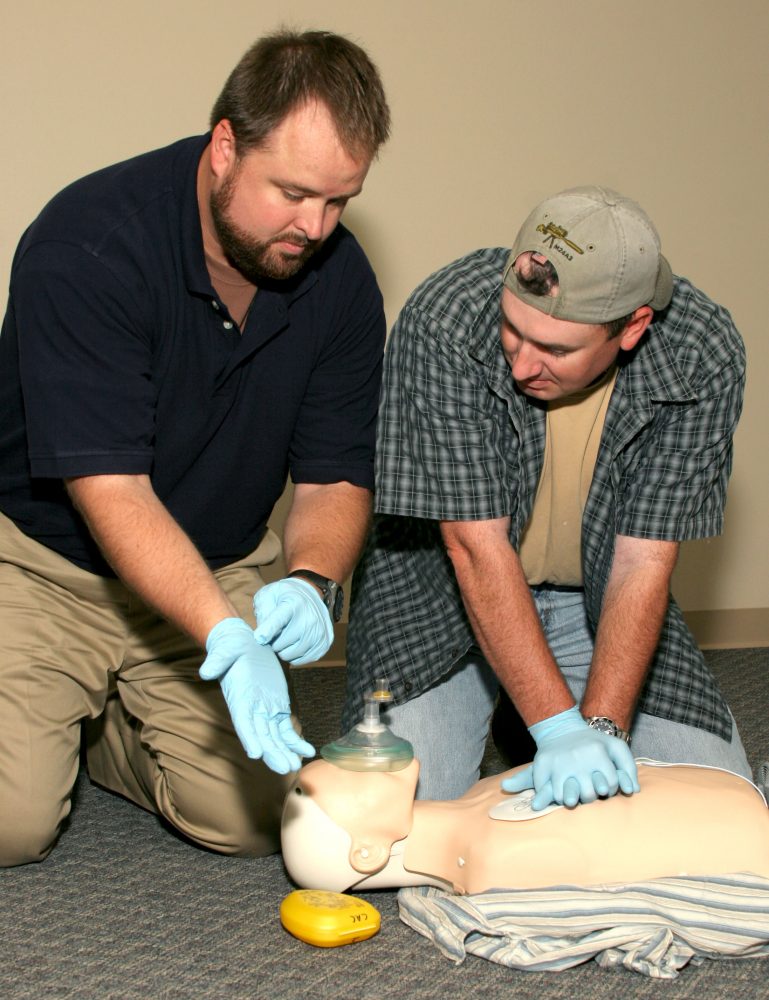

Students were paired up to take blood pressure and apply tourniquets and pressure bandages to one another.

TRAINING DAY ONE

Training Day One (TD1) began with the students signing in at Fossil Pointe Sporting Grounds in Decatur, Texas, our hosts for this weekend class.

The make-up of this class really brought home LSM’s desire to deliver their training to everyone: There were a dozen students of both genders between the ages of 10 and 50. A safety briefing was given to all attending. Then LSM made sure everyone had the address memorized so if a situation requiring medical attention arose, we would know where to tell dispatchers to go. We were then issued an individual first aid kit (IFAK) that included a tourniquet, pressure bandage, CPR mask, and practice hemostatic gauze.

The first thing Caleb got across was scene safety. If you are about to enter a scene, make sure it’s safe to do so. Just running into a scene is a great way to become another casualty, and that would only hamper the first responders. Caleb emphasizes empty hand, palms out, or “view finder.” This allows you to focus on your surroundings to make sure it’s safe to enter the scene. If it’s not, back away. This technique also presents a calming posture to anyone needing your attention, lets other responders know you are unarmed, and serves as a reminder to “glove up.”

Patient assessment was covered next. How is the patient presented to you? Is he bleeding, unconscious, or both? If the patient is bleeding, you must find the source(s). The LSM method of finding the source(s) is to perform a “blood claw” check by running your fingers like claws over the patient. This allows your gloved fingers to search for punctures, gashes and abrasions. We were shown how to check the level of consciousness (LOC): simply rubbing the sternum with your knuckles will tell you if your patient is unconscious or not.

CPR AND AEDs

We moved on to Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). The LSM team went over current American Heart Association guidelines for CPR. The AHA and LSM recommend 30 compressions to two breaths. The Medic-1 class is designed to be interactive, and the LSM team brought out several CPR dummies. We all took turns performing CPR on the dummies. The LSM staff not only critiqued our techniques, but also encouraged us.

After CPR, Caleb broke out a training Automated External Defibrillator (AED), and he and Kyle ran a demonstration on how to use it. This device is a true life saver, and knowing how to use it is a vital skill. Students took turns preparing the patient, applying pads, clearing others and ourselves away, and finally shocking. The practice AED would tell us to perform another shock or continue hands on with CPR.

TOURNIQUETS

The Medic-1 class moved on to controlling major bleeding. LSM cadre started with tourniquets and why they work. Caleb mentioned a manual that states that tourniquets should be the last option of defense to blood loss in the field. “If we agree that time is valuable in a life-threatening situation, why waste it by trying those techniques that may not work, but instead move right to something that will?”

We watched as Caleb quickly applied a SOFT-T Wide and the CAT Tourniquet to Kyle’s extremities while explaining the correct way to apply them. We went hands-on with our own practice tourniquets as we applied them to ourselves and in teams to one another.

Mike Effertz’s daughters applied tourniquets to him as he pretended to cry in agony. Then they reversed roles. “My daughters and I shoot and hunt together. I want to be able to help them in their time of need, and I want them to be able to help one another.”

Students were coached prior to CareFlite landing, and their performance was exemplary. Valerie Elishewitz assumes lead role as Mike Effertz guides Charlie Foxtrot 1 by hand signals.

PRESSURE BANDAGES

When we were confident in our abilities with the tourniquets, we broke out the pressure bandages. Caleb proclaimed, “If the patient gets a tourniquet, they are going to need a pressure bandage too.” We were shown how far bandage technology has come in the last decade. The pressure bandages preferred by Lone Star Medics are the Israeli Bandage and the Olaes Modular Bandage by Tactical Medical Solutions.

We removed our training pressure bandages from our class IFAKs. Some had Israeli Bandages while others had the Olaes. As with the tourniquets, we practiced on ourselves until we were confident, then took turns applying our bandage to our class buddy. Those with the Israeli Bandage swapped with those who had the Olaes, so everyone was able to see the plusses and minuses of both designs.

Finally we practiced what we had learned one more time. It was like a mid-term exam, and kept the class fresh. We found that our practice was paying off, as all students showed that they had not only listened to what they’d been shown and taught, but were able to perform CPR, use the AED, and apply tourniquets and pressure bandages without any trouble.

AnnaBrynn Effertz and another young lady begin their final test on TD2. Girls found SOFT-T Wide TQ and Olaes bandage easy to use.

TRAINING DAY TWO

First thing in the morning, we reviewed what had been covered on TD1. The cobwebs showed, but nothing was too difficult. TD2’s first new topic was another item in the IFAK—hemostatic agents. LSM covered where and when to use the preferred agent: Quik-Clot® Combat Gauze™, which requires correct application in order to work.

Caleb advised not to remove all the Quik-Clot Combat Gauze from the package, but to pull a little out at a time. The Combat Gauze comes three inches wide by four yards long. Leaving unused gauze in the package will show ER staff how much is in the wound.

LSM showed us how to apply the Combat Gauze. Like the other devices we used, the Combat Gauze in our class IFAKs was a training version of the real thing. As wounds vary in dimension, not only is packing the main cavity critical, but also any extraneous wound cavity. Once the wound is packed, three to five minutes of pressure is needed. If this doesn’t stop the bleeding, place more hemostatic agent in and pressure on the wound.

CAREFLITE

David Dunson provided a safety briefing on CareFlite, going into detail about how to contact CareFlite and what information they need. It also showed the viewpoint of the crew looking down at the vast green and brown Earth, and why knowing your location is so important. Simple things such as landmarks, intersections, or best yet, coordinates can help the crew on board the helicopter find you faster.

The correct way to approach a rotary-winged aircraft can also mean the difference between a safe casualty evacuation or more casualties. The briefing covered creating a safe landing zone (LZ). First find a large open area. Pace it out: 100 by 100 feet is the minimum for many air medevac companies. The LZ needs to be free of overhead obstructions such as power lines and tree branches, and free of debris which, when combined with the helicopter’s rotor wash, can become high-velocity missiles.

We moved outside and, with everyone’s input, established a safe LZ. A few minutes later, David announced, “Charlie Foxtrot 1 is inbound.”

As we awaited Charlie Foxtrot 1, a pair of LSM role players took over for the dummies as our patients. This was another reality-based scenario. Teams of four students plus an instructor began working on each victim, establishing an LOC, and applying tourniquets and pressure dressings.

The pilot circled the LZ, making sure it was of appropriate size and that there were no obstructions in or above the LZ. Once satisfied, he brought the aircraft into the wind on a steep descent and a smooth landing, as one team member from each team guided him with hand signals.

The Flight Nurse and Flight Paramedic exited the aircraft with their equipment at a 90-degree angle. Once outside the rotor coverage, they moved across the front of the aircraft. This allowed the pilot to keep them in constant view. We were instructed to follow the crew’s instructions to the letter. With the simulations completed, the crew returned to Charlie Foxtrot 1. The Bell 222 came back to life, lifted off to the south, performed a 270-degree turn and sped off to the east, returning to its Denton County base.

Students used all the equipment and techniques they’d trained on the previous day.

FRACTURES, BURNS AND POISONS

Back in the classroom, we learned how to handle open and closed fractures. Caleb and Kyle went over priorities for treating fractures with no bleeding. Many are quick to splint, when immobilization is actually the correct tactic. We used cravats in our class IFAKs to make slings. Caleb and Kyle also showed us how to control bleeding in the event of an open fracture.

LSM staff then covered the different types of burns, and the degrees of severity were explained in detail. Treatment of burns is rather limited. Simple dry, sterile dressings are the best way to deal with them.

Next up were poisons, toxins and venoms. In North Texas we have four venomous snakes, and area hospitals deal with dozens of snakebites every year. LSM again confirmed that so-called “snake bite kits” are useless. But some studies have shown a tourniquet applied above the bite may slow the progression of the venom. LSM suggests keeping the patient as calm as possible, marking the envenomation progression from the wound, and transporting the patient to an established collection point or LZ.

FINAL EXAM

With TD2 winding down, it was time for our final exams. We were each paired up with a partner and responded to a scenario. We didn’t know who we’d be paired up with until told to go, and we didn’t have any idea what our emergency would be.

I was paired with 10-year old AnnaBrynn Effertz, and our scenario was a person struck by a negligent discharge at a firing range. He was on the ground bleeding profusely from the leg and arm. AnnaBrynn had listened—she called 911. I began applying a SOFT-T Wide TQ above the wound and bandaging the wound. It was AnnaBrynn who noticed when the patient lost consciousness. She TQed the arm while I checked the patient, brought him back to consciousness, and checked for other wounds.

With that, our scenario concluded. We were critiqued by staff and others, told what we did well and what needed improvement.

The LSM staff kept the class loose and lively, providing an enjoyable experience for all. I realized early on the mistake I had made by putting off this kind of class in favor of firearms training. I now have a better understanding of how to treat grievous injuries and feel confident in my ability to help others and myself. I urge everyone to attend a medic course.

SOURCES:

Lone Star Medics

(817) 707-6887

www.lonestarmedics.com

CareFlite

(800) 442-6260

www.careflite.org

Tactical Medical Solutions

(888) 822-6331

www.tacmedsolutions.com

Fossil Pointe Shooting Center

(940) 393-6402

www.fossilpointe.net