The defensive 12-gauge shotgun is unique in the armory for its versatility. The slug, the typically one-ounce hunk of lead that converts the “shot” gun into an “unrifled” bullet launcher, allows the shooter to stretch out the effective range and connect with targets beyond shot or handgun range.

In other scenarios, the slug can give the shooter impressive penetration through barriers or large mammals where buckshot might not drive deeply enough. Slugs are alternately underrated or taken for granted without sufficient front-end prep work to reach their full potential.

We’ll walk through a few considerations to help the aspiring shotgunner.

Table of Contents

LOW RECOIL DOESN’T MEAN LOW POWERED

The slug market was driven for years by the big game hunting market, and marketing always places a premium on speed. The defensive shotgunner can shop with confidence on the low-recoil shelf. There is still plenty of power (and recoil) in low-recoil loads, but they are tailored much more to effective defensive use.

The exact recipe varies by manufacturer, but low-recoil slugs tend to be one ounce (approximately 438 grains) stepping out between 1,200 and 1,350 feet-per-second (fps). The numbers are a close match to the 1873 Springfield “Trapdoor” rifle government loading of the .45-70, which pushed a 405-grain bullet around 1,300 fps—a load that saw a lot of combat and slew a lot of bison.

The shotgun slug has low sectional density and a large frontal area, slowing quickly, but even as it crosses 125 yards, it is still a roughly .70-caliber bullet traveling at .45 ACP muzzle velocity.

Penetration with low-recoil slugs at distance is likely to be through and through, especially if a harder slug is selected.

Slug lets shotgun launch giant 438-grain bullet with surprising accuracy, giving shooter barrier penetration and distance. Clear Magtech slug gives good look at projectile to prevent confusing solid projectile with shot.

MYTH: SLUGS AREN’T ACCURATE

The traditional thought that riot guns can’t throw a group at distance makes sense. Tremendous effort and development have been applied to optimizing bullet shapes, rifling twists, sighting systems, etc, and still many rifles only group into several inches at 100 yards.

The remarkable thing is that in the range envelope that the defensive shotgun works best, most shotguns are capable of holding up to the task. It is entirely ordinary for a shotgun to print at least one slug load into fist-sized groups at 100—this without any rifling and no sights in the traditional sense. It is not uncommon for a shottie/choke/slug combination to print groups that would do an open-sighted .30-30 proud.

At the more common employment range of 50 yards, it is unremarkable to find a combo that has the giant holes touching.

Slugs can shoot, as this 50-yard group with Magtech S&B shows. Target also demonstrates need to zero, with six o’clock aim point impacting eight inches off before adjustment.

THE CATCH

Alas, there is a good reason that the inaccurate notion sticks. The shooter must do the hard work of testing slugs in order to find the magic combination of reliable cycling (semiauto), acceptable recoil, accuracy, and point of impact relative to point of aim. Shooting group after group from a shotgun from prone or bench is uncomfortable enough to scare away all but the most serious.

Due to the notion of inaccuracy, the shooter likely stops after the first halfway acceptable result and moves on. This is more likely if previous attempts yielded hairspray or potato-cannon level groups. It happens.

Shotguns seem to be more fickle about load preference than the worst prima donna rimfire. This makes the journey both interesting and maddening, with an impossibly small group starting followed by another shot that flies wide, very wide, and shakes the shooter’s self-esteem.

There is a randomness inherent in the tolerance stack of rough sighting system, smooth bore, slug consistency/QC, and greater possibility of flinch that challenges even the best shooter.

Although there are slugs that have a reputation for accuracy, every shotgun is somewhat of a snowflake in its individual preference. Newer slug designs like the Fiocchi Aero or Federal Truball may live up to their reputation in most barrels, while plain traditional Foster-type slugs may be the hot ticket in another.

I have found that if a combination groups really well, it tends to be pretty consistent, whereas the several in/several out grouping of others can have variable results. In the long run, it is probably better to have the combo that groups five inches all day at point of aim than the load that puts two touching every third group on an odd-numbered day while flinging the rest to parts unknown.

Shooters can dispel most misconceptions about slugs by putting in effort to lay down and get data from the shotgun/slug/choke combo.

MYTH: RAINBOWS?

The shotgun slug is often said to have a “rainbow”-like trajectory. It depends on how you look at it. The slug is really at its best from the muzzle to 125 yards in most hands. Beyond that, from field positions, the groups are opening up to a point where hit probability deep dives and the projectile starts to drop rapidly. That is the deal. A lucky gunner might fling a “punkin’ ball” out and connect at 200, but you wouldn’t want to have to count on the hit for mission success.

But inside that 125-yard arc, the slug is flying almost a perfect match of .357 or .44 Magnum pistol trajectory, both of which are considered flat-shooting, long-range handgun rounds. Zeroing the shotgun about an inch and a half high at 50 yards puts the slugs kissing either side of line of sight out to 100 yards.

Most bead-sighted guns are likely to have an approximate 100-yard zero, which runs about three to four inches high at the more common 50 to 75 yard distances, leading the unknowing to mistake trajectory for inaccuracy.

Stepped rib with bead is a fast arrangement that allows surprising precision, much like an express sight.

CHOKE UP

Choke changes the final constriction on the barrel ever so slightly, effectively serving as the muzzle crown for slugs. Most combat shotguns are choked cylinder (no constriction) or improved cylinder (IC), with skeet fitting in between the two and light modified (LM) being slightly more constrictive for those experimenting. Each “tighter” choke adds .005 inch in constriction and adds another three to five yards of dense pattern with shot.

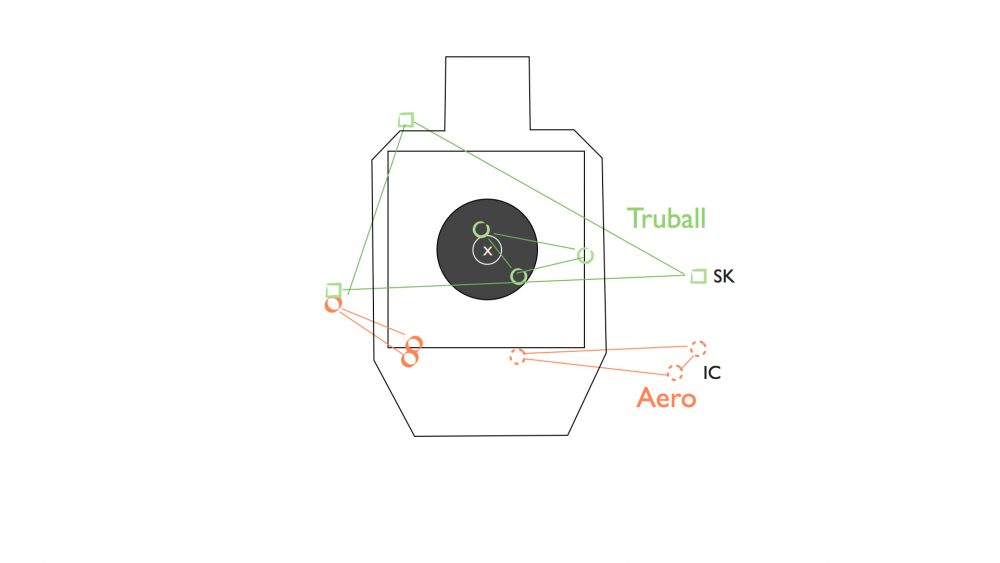

Changing the choke can have a dramatic effect on slug grouping. I find that choking up or down can shift the point of impact and/or tighten or open the group. In the example illustrated, changing from Skeet to Improved Cylinder (a very small change in constriction and pattern) shifted the group center over a foot laterally with one slug and took the best overall performing point of impact/group size load and opened it up to where the entire group bypassed the 12X20-inch target to three cardinal directions. Dramatic!

Changing chokes often changes point of impact and/or affects group size. Small change in choke turned the best load into the worst (green) and shifted impact by a foot at 100 yards (orange) with different slugs.

This knowledge gives the shooter two broad options. If the shotgun has removable chokes, and the shooter likes the terminal performance, reliability or availability of a certain slug load he can group with the four “practical” chokes until the sweet spot is found. For those running a fixed choke gun, the quest becomes to find the right slug that agrees with that barrel.

For the individual shooter, there are a lot of benefits to having interchangeable chokes to tailor performance and take full advantage of the shotgun’s versatility.

For any organization with over five shooters, removable chokes are a predictable headache that will inevitably lead to chokes rusted in place, chokes missing, full chokes in the gun by mistake, etc, explaining why “combat” shotguns tend to have fixed choke barrels.

LINING IT UP

The defensive 12 is at its best while at its most versatile, with a fairly open choke that allows the shooter to take advantage of the pattern with shot, and simple sights that let the shooter see as much as possible.

I prefer a good stepped rib and bead front, which gives me as much field of view as possible where the shotgun is most used and allows express-like sight precision at distance. A very few shotguns have good low-profile open sights that work well too.

Many military-style aperture sights suck up field of view with sight housings and protective wings and feature apertures that are distracting at max speed and not much more precise at distance than the preceding options.

Some shotgunners custom mount their preferred pistol sights into the shotgun rib, which involves cost and effort but works well. The simple round bead and receiver groove on bare-bones guns works with effort but is far from ideal.

Slug recoil can be controlled and even applied rapid fire through technique. Steve Fisher of Sentinel Concepts fires last slug in five-shot drill.

BAD ASSUMPTIONS

For years the shotgun has been issued to police and military alike with little to no effort to zero or group beyond 25 yards. Often the 12 is not individually issued, instead rotating on post or with a vehicle, so that the weapon that was trained on is not the one in hand when the shooting starts.

This is a recipe for lackluster results with anything, but particularly so when trying to stretch the shotgun to 50+ yards. It’s been my observation that shooters running slugs that haven’t been carefully grouped/zeroed connect with silhouette-sized targets about 80% of the time on demand at 50 yards and lose 10% probability with every ten yards beyond that.

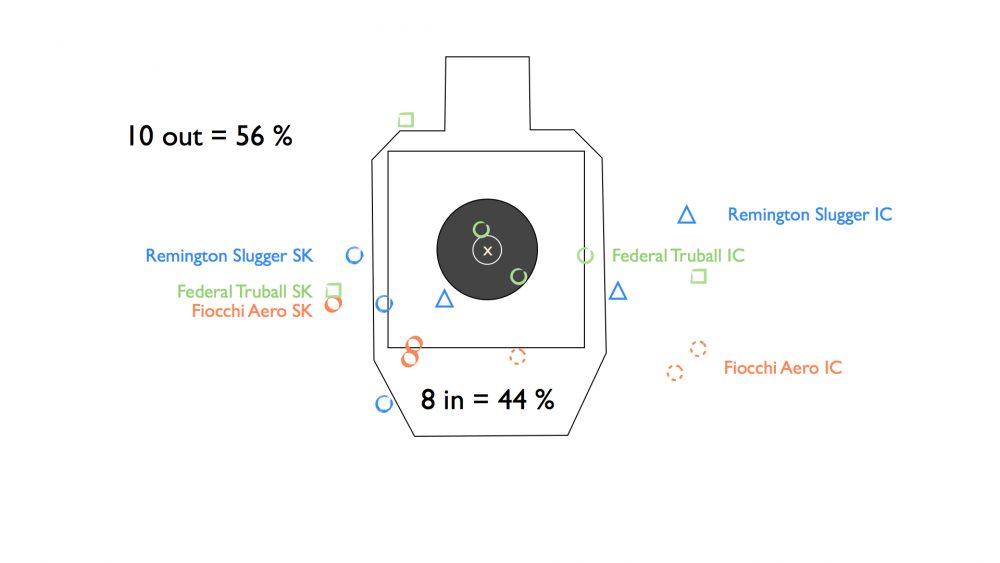

As one example, the illustration charts the composite of three different loads grouped with two different chokes, each three-shot group aimed at the six o’clock point on the 5.5-inch bull. Only one of the six combinations put all three into a torso-sized silhouette. And without adjusted aim points for the actual point of impact, only 44% hit the silhouette at 100 yards, and this was from prone over a rest.

Composite of (6) three-slug groups; Remington Slugger, Fiocchi Aero, and Federal Truball with Skeet (SK) and then Improved Cylinder (IC) chokes. That only 44% hit the torso-sized target speaks to the need to group/select the best load and then zero or establish offset aim points.

BUCK OR BALL?

I’m sure somewhere there’s a serious duty user who has a shottie that he knows exactly where the offset aim point is as well as the expected group size with the duty slug in 20-yard increments. But finding that fraction of 1% is like finding Bigfoot—he’s out there, just hard to find to prove it.

I recently took an unzeroed Beretta 1301 Tactical and fired one shot each with a slug and Federal’s FliteControl Buckshot at 55 yards over the hood of a vehicle. I called the shot as a perfect center hit, but the slug was a scratch hit to the trapezoid/neck junction, while the FliteControl buck put an impressive five pellets into the vitals.

That was not at all what I expected, so I patterned more of the FliteControl buck as well as some Hornady Critical Defense buckshot with its VersaTite wad. Even out at 55 yards, the improved buckshot loads put between two and six pellets into the C zone (12X18-inch torso), with four being the average.

On two separate groups, three of the pellets struck the A zone. This is pretty remarkable, more so coming from a cylinder bore gun. With traditional buck, getting any hits past 30 yards on a C zone would be noteworthy, as the pattern would have hollowed out and “donuted” the shot around the target. The new loads challenge conventional wisdom.

With an unzeroed 12 gauge, there is some merit in considering staying with improved buck loads farther than the previous standard of 20 to 25 yards. In this case with that particular shotgun, I was very surprised to find I would have been better off with the buckshot.

PISTOL, SHOTGUN, RIFLE?

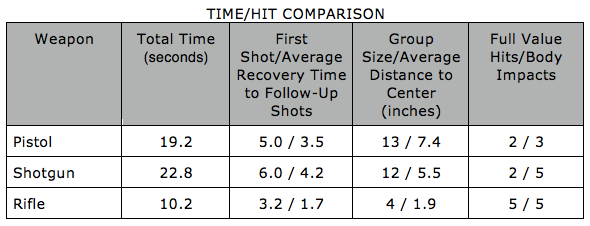

For a simple comparison of a long-range threat, I set up one of the new USMC MMPS-1 silhouettes at 70 yards.

Using a Glock 9mm, Benelli M2, and BCM AR with Bushnell Elite 1-6.5X optic, I fired five shots for time with all three weapons from standing, firing as quickly as I could recover and be confident of a hit.

The table pretty much sells the patrol rifle concept, with the BCM putting five of the excellent Black Hills 77-grainers into a baby fist-sized knot in the heart area of the silhouette in only ten seconds—less than half the time of the scattergun.

The pistol was a last-minute addition, and the cheap practice ammo on hand did not shoot as well as the situation demanded but is pretty representative of what a pistol can do in many hands.

The Benelli put two Remington Sluggers in the “good stuff,” two solid lung hits, and one crease across the shoulder that might have drawn blood.

Slugs add a unique ballistic capability to the riot gun. For those who choose or carry the shotgun, the effort in working out the quirks can double or triple effective range.

However, for those who simply cycle a slug into the gun and expect to hit at distance, there may be an exaggerated sense of capability.

SOURCES:

Black Hills Ammunition

(605) 348-5150

www.black-hills.com

Bravo Company Mfg.

(877) 272-8626

www.bravocompanymfg.com

Bushnell Outdoor Products

(800) 423-3537

www.bushnell.com

Federal Premium Ammunition

(800) 379-1732

www.federalpremium.com

Hornady Mfg. Co.

(800) 338-3220

www.hornady.com