In the prior two issues we covered conversion kits that enabled the .22 Long Rifle (LR) cartridge to be fired in firearms designed for larger cartridges. If you believe—like I do—that the .22 LR round is an economical way to practice, your local range is probably littered with the small cases by now. You have two choices: leave them lie or recycle them into jacketed bullets for reloading into .223/5.56mm cases.

That’s right, with the right equipment you can indeed make the proverbial silk purse from a sow’s ear and turn “useless” .22 LR cases into quality .224 caliber bullets.

This is not new technology—in fact a couple of well-known ammunition manufacturers started out in the business by making .224 bullets from .22 cases.

Imperfections, while important to most cast bullets, are not a concern with core castings, as they will be removed during the high pressures of swaging (top), leaving a perfect, cylindrical core. Anything above the weight desired is ejected from the swaging die as thin sprues.

Table of Contents

CORBIN BULLET SWAGING SYSTEMS

If you own a sturdy reloading press—such as the RCBS Rock Chucker—you already have one of the necessary pieces of equipment. The dies needed to transform the empty .22 cases into .224 caliber bullets are available from Corbin Bullet Swaging Systems.

A complete kit available from Corbin includes a Rimfire Jacket-Making die; a four cavity, .185-diameter core mound; a Core Seat die and a Point Forming die; Corbin Swage Lube; and a copy of the Corbin Handbook of Bullet Swaging, No. 8, which has full instructions and illustrations.

For very precise weight control, you can order an optional Core Swage die, which bleeds off surplus lead from the molded lead cores. I highly recommend this die for making the most accurate bullets possible.

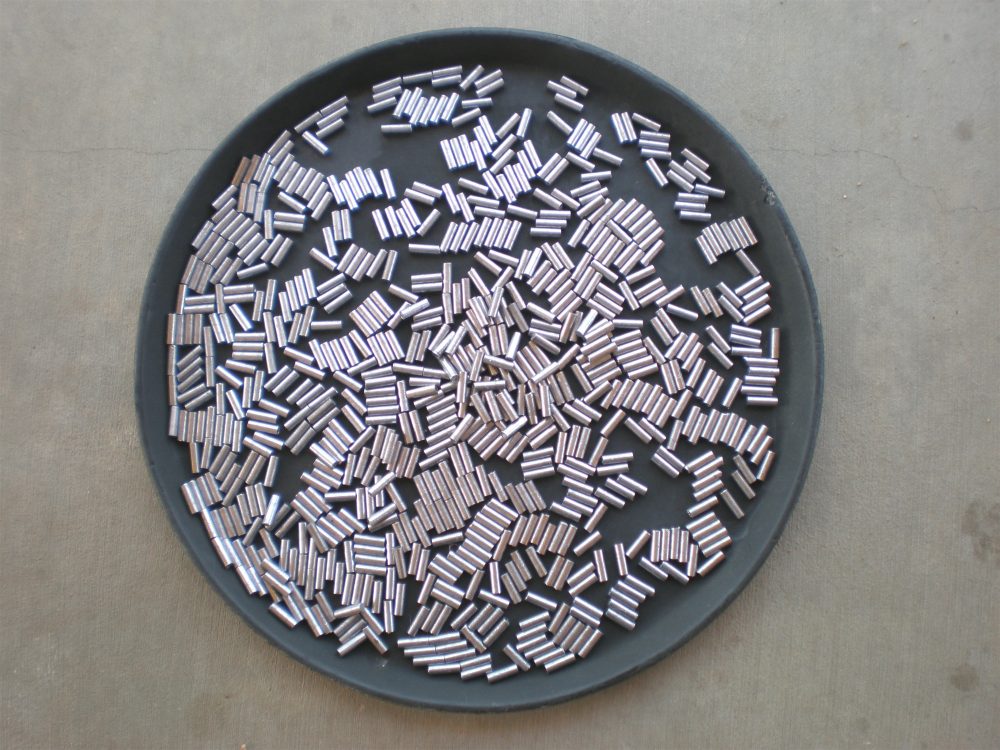

Over 500 swaged cores ready for seating in prepared .22 LR cases.

MAKING BULLETS

An advisory note is in order here: all .22 LR cases are not equal. Measuring cases from different manufacturers, I have noticed differences from .61” to as long as .68”. If possible, it is preferable to use cases from the same brand—if not the same lot—for the best consistency.

Once you have assembled a quantity of .22 LR cases, the first step is to boil them in a pan of water with a small amount of detergent to clean them and remove the primer material from the rim of the cases. A tip I picked up from Corbin’s website is to add an ounce of vinegar and a spoonful of salt to remove tarnish from the cases. Rinse the cases well with clean water after they have been boiled.

The next step is to relieve stress in the cases by heating them. Corbin advises that they may be put in a self-cleaning oven, but I have not had much luck with this method and had many bullet points crack and fold over during the point forming step (see below). The method I use is to place the cases into an old cake pan and heat them with a propane torch until a faint red glow is detected. It is best to do this in a dark room to avoid overheating the cases.

The cases are now lubed and run through the Jacket Maker die. This step swages out the rim of the .22 case, leaving a perfect cylinder ready for a core to be seated.

Using just any fired .22 LR case may result in inconsistent bullet weights and finished size. Although barely noticeable to the naked eye, case on left measured .64” and case on right measured .61”. Case on right, however, has thicker brass—weighing .6 grains more as measured on MTM Mini Digital Reloading Scale—and will make better bullet jacket.

There are two ways to go about obtaining the necessary lead cores: use the Corbin four-cavity mold, or buy lead wire and cut it into lengths. Personally, I use the core mold. You must use pure lead, as wheel weights and other lead with antimony are too hard to swage and may damage your dies. If you go the mold route, be sure to melt the lead and cast the cores in a well-ventilated area, and take other precautions such as washing your hands with cold water before handling food to avoid possible lead contamination.

Before I seat the cores, I take one of the cases I will be using and, using the abovementioned Core Swage die, I adjust the die slowly until I achieve the exact weight bullet (core and jacket combined) that I want, using an MTM Mini Digital Reloading Scale to verify the weight. This step can be tedious, but once the die is adjusted, it goes fairly fast and is well worth the extra time.

The next step is seating the cores. Place a jacket into the die, insert a core and lower the handle on the reloading press until pressure is felt. Continue to adjust the die until a small lip of lead can be seen forming around the inside circumference of the jacket.

Next comes the forming of the bullet’s point. For hollowpoint bullets, lube the jacket and place the open end down into the die. For full metal jacket bullets, lube the jacket and place the base of the bullet into the die. Lower the ram of the press all the way. This step takes a fair amount of pressure, thus the recommendation for a sturdy press. The bullet will be ejected from the die as the ram is raised.

Finally, if you plan to reload for a semiautomatic firearm such as an AR-15 or Mini-14, the bullet should have a cannelure to ensure it is not pushed back into the case during the loading cycle. Corbin’s hand cannelure tool makes it easy to apply a cannelure to the bullets. Once this final step has been completed, you’re ready to start reloading your “free” bullets.

With care, weight of bullets can be very precise. This core and empty case will be used to make a .60-grain, .224-caliber bullet.

GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS

The good news is that, after you have purchased the necessary dies, the bullets you make will be free (except for your time). The bad news is that the dies are not cheap.

Currently the cost of Corbin’s Rimfire Jacket Maker kit is $783, the optional Core Swage die is $198 and the hand cannelure tool is $129. At the going rate for factory .224 caliber bullets for reloading, one would need to make close to 10,000 bullets before he would begin to see a return on the investment. Therefore, the price of dies may be out of reach for a single individual, but well suited for clubs. For a peace officer, the dies may be tax deductible under training.

Left to right: unfired .22 LR cartridge, case with rim swaged out and core seated, formed bullet, formed bullet with cannelure, reloaded .223 cartridge.

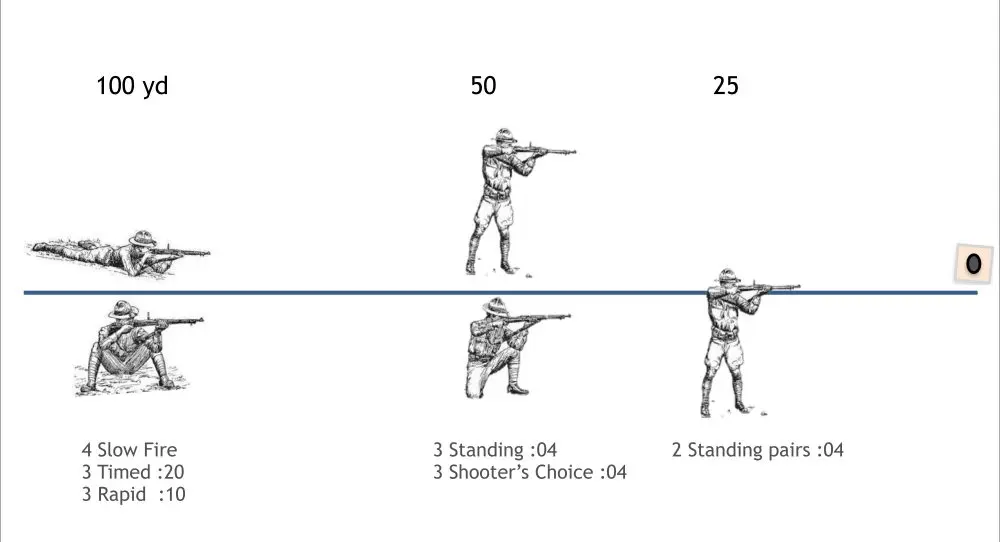

How accurate the final product is depends on many things: consistency in jacket and core weight, pressure put on the bullet during the cannelure process (too much pressure on one side may create an unbalanced bullet), consistency in powder charge weight, your rifle’s barrel, etc. With care, however, two to three-inch groups at 100 yards should be doable.

Finally, regardless of what savings one may realize, the above process is tedious. If you look at reloading as a chore and the sole reason for doing it is saving a few bucks, you’ll likely hate it. Personally, I find time alone at the reloading bench to have a calming, therapeutic effect, and I enjoy it very much. If you are of the same mind and enjoy rolling your own, you’ll probably get a kick out of turning .22 LR cases into shiny new .223 bullets.

SOURCES:

Corbin Bullet Swaging Systems

Dept. S.W.A.T.

P.O. Box 2659

White City, OR 97503

(541) 826-5211

www.corbins.com

MTM Molded Products Company

Dept. S.W.A.T.

3370 Obco Court

Dayton, OH 45414

(937) 890-7461

www.mtmcase-gard.com