British colonists arriving on America’s shores discovered a lot of inhospitable things. Rocky soil and nasty weather in the north. Malaria in the south. And eventually hostile natives everywhere. Among the many unfriendlies were rattlesnakes. Colonists on the north coast encountered the timber rattlesnake. Those farther south had to deal with the eastern diamondback, the most massive pit viper in the world.

Britain has one type of venomous snake, the adder, and of course humans have known and feared various kinds of poisonous serpents through all of history. But rattlers? Those were something new to Europeans and uniquely American. Here was a deadly snake that, like most snakes, just wanted to be left alone. Yet if you got in its face, it would politely warn you before striking.

Long before the bald eagle or the female figure of Columbia came to symbolize America, and decades before there was a United States, colonists began adopting the rattlesnake as a symbol of their new land.

The snake first turned up as a published symbol of defiance in 1751 in the clever words of Benjamin Franklin. At that time, British authorities had a habit of transporting prisoners to the American colonies and turning them loose. While some of the prisoners were harmless, others brought mayhem and death. In an essay dripping with sarcasm, Franklin wrote that the colonists should repay the mother country by rounding up rattlers and “Have them carefully distributed in St. James’s Park, in the Spring-Gardens and other Places of Pleasure about London; in the Gardens of all the Nobility and Gentry throughout the Nation; but particularly in the Gardens of the Prime Ministers, the Lords of Trade and Members of Parliament; for to them we are most particularly obliged.”

Franklin noted that, as usual, Britain would be getting the better end of the rattlers-for-convicts trade: “For the RattleSnake gives Warning before he attempts his Mischief; which the Convict does not.”

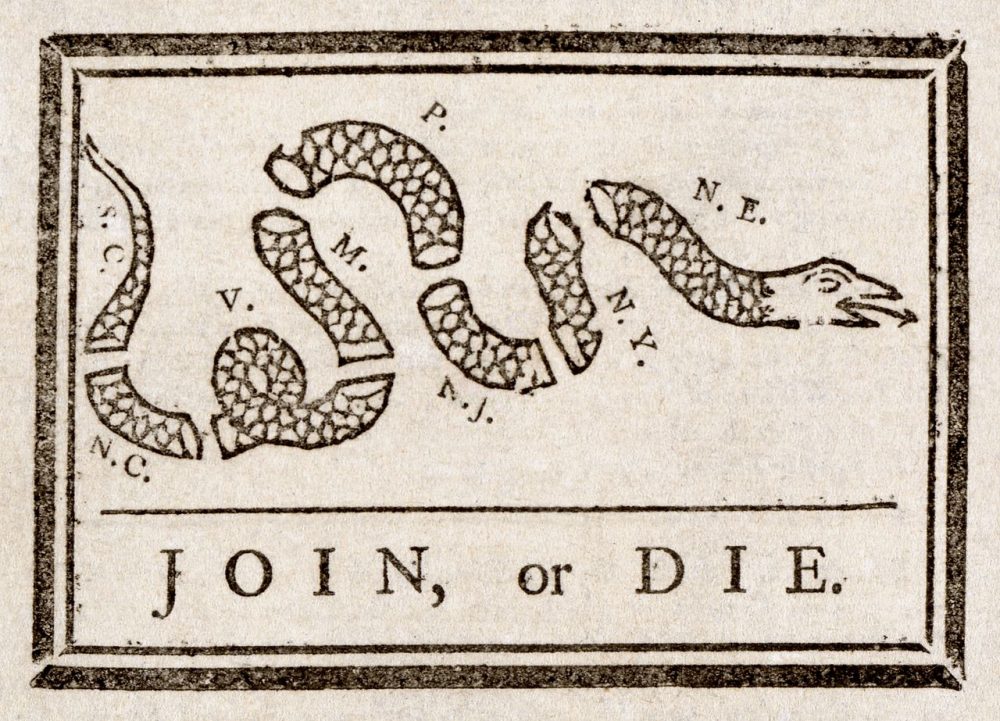

Three years later, Franklin immortalized the rattlesnake in American iconography. On 9 May 1754, his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, published the first editorial cartoon in North America. The now-famous “Join or Die” engraving showed the colonies as a rattlesnake divided into segments. The French and Indian War was pending and Franklin’s message was that the colonies needed to unite to fight—unite with each other and with the British against mutual enemies.

But oh, how a few years can change matters! Just 11 years later, Franklin’s segmented serpent took on a whole new meaning—and shortly thereafter, the rattlesnake became whole again.

In 1765, without the consent of the colonists, Britain passed the Stamp Act. It was an attempt to force Americans to pay for the recently ended war. To say this didn’t go down well would be an understatement. You surely remember the phrase “No taxation without representation!”

What’s less remembered is that Franklin’s divided snake became a symbol among American radicals. Until that time, despite any grievances they had against England, the vast majority of colonists considered themselves loyal British citizens. The notion of independence had entered only a few heads. After 1765, that began to change.

Radicals used Franklin’s symbol to urge colonists to unite against their English rulers. The unstated message became: The wisest course for Americans is to preserve the eternal value of liberty by defying British tyrants.

Loyalists, of course (who still constituted the majority among colonists) looked at the serpent and saw something more biblical—disobedience, slithering connivance, and treachery.

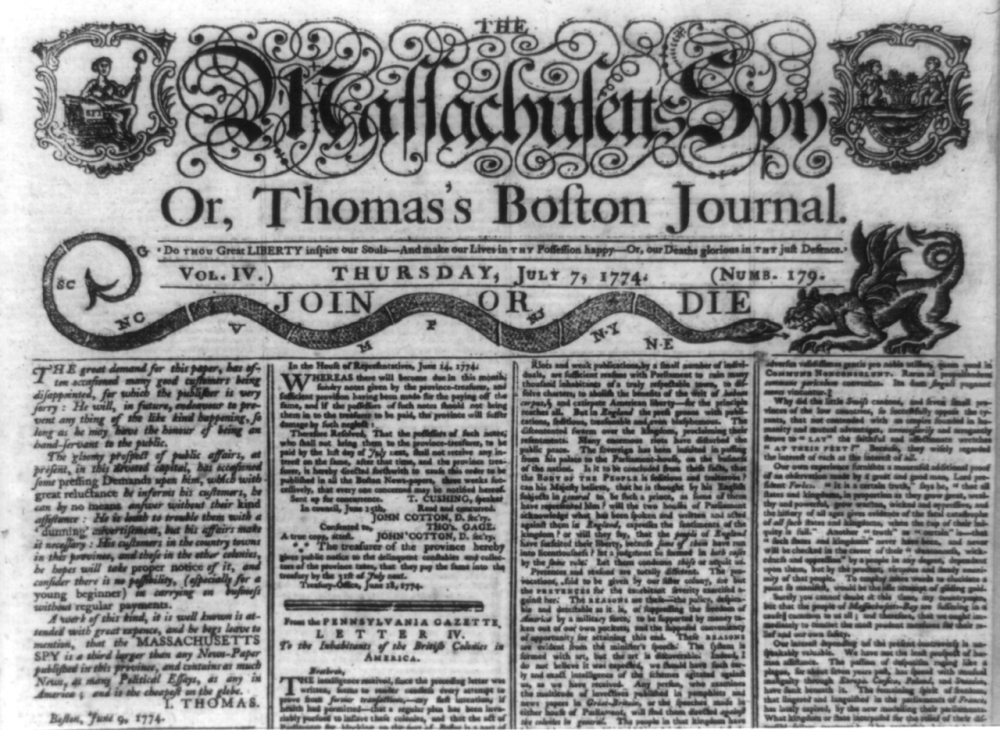

In 1774, Paul Revere united the segments of the serpent and added it to the masthead of another newspaper, the Massachusetts Spy—where he portrayed it battling a dragon (one of the heraldic symbols of England). The next year, as we all know, the British perpetrated the (in retrospect) extremely stupid move of trying to disarm the colonists. At Lexington and Concord, the colonists replied, “No and hell no.”

That same year, 1775, Colonel Christopher Gadsden, a member of the Second Continental Congress charged with outfitting a new American Marine Corps to accompany its new Navy, designed the famous yellow flag we know today, with its coiled diamondback (with 13 rattles representing the colonies) threatening to strike, and the motto “Don’t Tread On Me.”

At about the same time, the first contingent of Marines formed in Philadelphia, and they were seen bearing drums with the same colors, snake, and motto. Whether Gadsden borrowed the design from them or they from him is a chicken-and-egg problem. In fact, to give an idea just how truly American the rattlesnake emblem is, there were five different Revolutionary War flags that used a rattlesnake design.

But that December, Gadsden gave one of his flags to the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the Navy, Commodore Esek Hopkins. The flag became the commodore’s personal standard—and, some would claim, the first true American flag, even before the stars and stripes.

Well, there are quite a few flags that might claim “firsts.” But certainly the rattlesnake flag is unique in the way it expresses the traditional American character: We’ll leave you alone if you leave us alone, but mess with our freedom and we’ll bite.

Eventually we forgot all that. The Gadsden flag became a curiosity, relegated to color illustrations of historical U.S. flags. Libertarians still cherished it, as did some Southern good ole’ boys (Gadsden was from South Carolina). I used it on the cover of one of my books, Hardyville Tales (the residents of my fictional town of Hardyville have flown the Gadsden flag for 200 years). But otherwise, the great American flag was seldom seen. Then came the Tea Party movement.

At first it was heartening to see the bright yellow flag waving everywhere and appearing on stickers, hats, and protest signs. The U.S. federal government has become far more tyrannical than, and at least as arrogantly oblivious as, the long-ago British government of George III. We need the Gadsden flag and what it represents.

But what it represents today is a different matter.

The Tea Party movement is diverse and decentralized—which is good. When it took off in 2009, it was very much a liberty movement—anti-tax, anti-bailout, anti-cronyism, anti-big government, and pro-freedom. It was a worthy heir to a longstanding libertarian tradition (some of us used to send tea bags to politicians to remind them that Americans once dumped tea in Boston Harbor—then dumped tax-imposing rulers).

But precisely because of the diversity and decentrality of the Tea Party movement, it was easy for anybody with an anti-Obama agenda to swoop in and co-opt both the symbol and the movement. The Republican Party got busy attaching itself to the Tea Party. So did others. Pretty soon, the Tea Party’s initial purpose was lost in a sea of agendas. Now it’s easy for liberals and the media to tar the movement—and its glorious Gadsden symbol—with the broad brush of “right-wing crazies.”

While the anti-tax, small-government core remains, nobody can say what the Tea Party really stands for today. Anti-abortion? Religious fundamentalism? Hardcore Republican partisanship? Obama “birtherism,” 9-11 “trutherism”? Militarism? Anti-Islam? Vague, generalized patriotism? Whether you’re for or against those things, they have nothing—nothing—to do with the fundamental meaning of the defiant rattlesnake flag. All those agendas have become an ignoble, chaotic diversion from the core thing we need to remember—and ultimately need to do.

The “Don’t Tread On Me” rattlesnake means just one thing. It has one very focused, very clear message that should never be forgotten, not by We the People, and not by those who crave to rule us: Let us live as we wish and there will be peace between us. Threaten our freedom and we will strike back.

The enemies of freedom will never love us. They may well view us as disobedient (which we are), conniving, and treacherous (which we aren’t). Let them consider us dangerous. But we should give them no reason to think that “our” flag, the original American flag, stands for anything but self-defense in the cause of liberty.

It’s sad what’s happened to the glorious Gadsden in the hands of politicians, agenda-seekers, and a scornful media. Perhaps it’s time for a re-design. In fact my online friend Kent McManigal has provided a worthy successor, a flag for our time. Its official name is the DullHawk flag. It’ll probably become better known by its motto: