Stacking up—entering a room to conduct close-quarters battle (CQB)—is one of the most dangerous tasks a Soldier or law enforcement officer may have to face. Some of the hardest CQB fighting U.S. forces faced was during the U.S occupation of Iraq in the mid-2000s, from the 1st and 2nd Battles of Fallujah to taking on the Mahdi Army in Baghdad.

With Iraq being a generally flat desert country, insurgents made good use of the only cover available—urban terrain. During these urban operations, Special Operations realized the standard CQB techniques that had been around forever were not getting the job done based off the four-man room clearing method as outlined in Battle Drill 6A (of the Army’s Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad Manual).

The techniques were unnecessarily exposing friendly assaulters to enemy fire. As a result, by 2006 U.S. Army Special Forces started implementing changes to the SOP on room entry and CQB to meet the real demands of urban fighting. This begs the question, “Why did the standard techniques not work so well in the first place?” One reason is the fact that U.S. military CQB techniques have their roots in hostage rescue (HR), not CQB, where destroying the enemy is the priority.

Table of Contents

CQB AND HOSTAGE RESCUE

What is the difference between HR and CQB? Unfortunately, even in the military, many do not know. Even worse, many think there actually is no difference between the two. Here’s the key difference:

In HR, the hostage comes first, while in CQB, the friendly assaulter’s own life is important. As previously mentioned, the Army’s foundation for how to conduct room clearing is Battle Drill 6A, based off a four-man team (or stack).

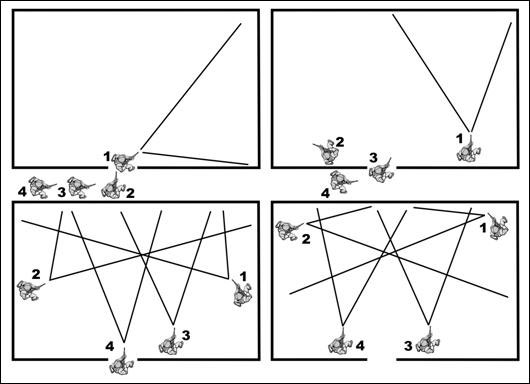

Battle Drill 6A directs how each team member should enter, and the responsibilities and sectors each member of the stack should focus on and clear. The method relies on all four members of the team entering the room almost simultaneously, flooding the room with assaulters, with crisscrossing sectors of fire covering all threats. Sounds good, right? Unfortunately, this is HR based, not CQB based.

In order to flood the room with maximum speed with all four team members, it relies on the number one and two man entering the room and clearing their corners first before engaging any targets in the center of the room. This is basically to make a safe pathway for the number three and four man to enter and shoot any threats in the center of the room.

But just how is this HR? Because the number one and two man are drawing fire and making space for the rest of the team to come in. The whole purpose of the team rushing in (flooding) the room is to draw attention off any hostages and force all bad guys to turn their attention to the team flowing in.

Rapidly filling the space with the assault team forces threats to focus on them and limits the reaction time to kill hostages. Success is based off the team surprising any bad guys as they enter.

Well, in full-blown urban combat, after you clear one or two rooms in a building, if there are more to clear, chances are the enemy now knows you are coming. No matter how fast a team might be able to enter and flow into a room, it’s not fast enough to outpace AK bullets being fired from waiting and prepared insurgents.

MISCONCEPTION OF IMMEDIATE THREAT

Not buying this yet? Let’s look at the specific instructions written in 6A for the number one and number two man with regard to shooting targets. 6A states, “Number 1 and 2 man’s job is to enter the room, eliminating any immediate threat. Turn and clear corners.” What exactly is an immediate threat? According to the Special Forces manual on Advanced Urban Combat, it is an individual (threat) who blocks access into the room.

This means someone standing in the doorway at arm’s distance who physically blocks the path to get into the room. So unless a threat is at arm’s distance, one and two man do not engage. They must clear their corners before they can engage. But what if the threat is on the far wall center of the room shooting at them as they make entry? The answer is no.

According to 6A and what I have experienced throughout my years of training (both regular Army and SF), the job of engaging any center threats beyond immediate threats falls on the three and four man. For the one and two man, the importance is on getting the entire team in the room to “flood” it. In other words, getting bodies into the room is important, not killing the enemy. This is HR, not CQB.

Proponents of 6A will be quick to point out that a well-trained team will enter fast enough so there is almost no gap between the one and two man entering and the three and four man. Center threats will be taken care of. Perhaps, but in real-world practice, even if it’s just half a second or so, that is still time the one and two man are walking into a room filled with bad guys and ignoring center threats for the sake of checking the corners first.

If there is a threat shooting at them from the center of the room, wouldn’t it make sense for the number one guy to try to take him out as he enters?

Perhaps, but now the issue is you are relying on that number one man to be able to break from his training and perform under stress. That’s a technique counter to his training, which is shoot at a threat deep in the room while moving through a door, prior to turning to clear his corner.

Of course, this is the exact situation Special Forces soldiers had to deal with while conducting operations against insurgents during the height of the fighting in Iraq. Regardless of the distance from the door or if they are an immediate threat or not, if you want any chance of getting in and clearing out the room without taking friendly casualties, you must deal with visible threats as soon as possible, no matter where or how far into the room they are, before you try to make entry.

I will not go over in detail the exact changes that were made to the Army’s room-entry SOP, because some of these techniques are still being employed by Special Operations. Instead I want to offer ideas to take into consideration if you are a member of a military or law enforcement team where CQB is part of your mission set.

LET THE BULLET DO THE WORK FOR YOU

Why rush into a room when bullets can get there a lot faster? Prior to making room entry, the number one man should be afforded the opportunity to “pie off” as much of the room as possible, shooting threats as he sees them. There is no need to try to dominate space with friendly bodies if no hostages are involved. Speed should come instead, in the form of how fast you can put lead into targets, not how fast you can rush into a room.

A few different techniques have been adopted that allow the one and two man to pie the door prior to entry. But whether it’s a fast or slow pie off, it should permit the shooting of any readily visible threats prior to entry—regardless of how deep into the room they may be standing. This change has been much more effective at both surprising the enemy and reducing the chances of the bad guys having time to focus on the team as they make entry, turning the doorway into the dreaded fatal funnel.

I’m not advocating limited penetration, where the team crowds around the door and shoots in (Israeli method). Hanging out in the doorway is never a good idea, but before the team commits to making entry, why not put bullets in there first?

It’s a heck of a lot safer for number one man to not have to rely on his teammates to shoot any center threats he is forced to ignore before his corner is cleared. Instead, he can now pie off as much as he can see and put bullets into bad guys, then make entry and clear his corner.

THE FOLLY OF THE FOUR-MAN STACK

Another change was a plus-up of the size of the entry teams, from four to five and even six-man teams. The problem with a four-man team is they can find themselves outnumbered or outgunned upon entry. Only in training does it seem there is just one bad guy per room. This has actually created a training scar in many units.

This is not as much of an issue for law enforcement, even in active-shooter scenarios. Most times, the threat is limited to one or two shooters. But for military units, the idea that the enemy will conveniently spread out their force in one-man increments throughout the building is incorrect. In real life—especially if you lose the element of surprise—the enemy will probably be occupying rooms in small groups.

Just like how U.S forces are trained to hold buildings by strong points such as a room or floor—filling it up with soldiers covering all windows, doors, and openings—the enemy will do the same if they want to resist being taken. Plus it’s just human nature to want to stick together when faced with danger. If you are taking fire from a building or room, more than one bad guy is likely in it.

A four-man team may not be enough to have both a numerical advantage and firepower dominance upon entry. Also, who says they just have pistols and rifles? In both Iraq and Afghanistan, light machine guns have been encountered in hallways and entryways into buildings, with the intent to destroy any teams attempting room entry. In these cases, you probably need more than a four-man team to suppress it.

The biggest deficit with four-man teams is the inability to cover all the angles the team will be exposed to as they conduct room clearing. If CQB is being conducted correctly and the building is being swarmed by half a dozen four-man teams, it’s not such a big issue. But if the four-man teams are spread out by even just one room’s distance or across a hall, it can leave gaps in coverage that the enemy can exploit, no matter how fast a team can flow into a room.

The danger will come from being shot by a bad guy hiding a few doors down, from a connecting or adjacent room or across a hall. That is a huge problem. Unless your unit practices shooting from one room to another, more often than not, assaulters only focus on the room they are entering. This can be a fatal mistake.

The bottom line to ensure that long angles, open doors, and adjoining rooms are covered is that it takes more than a four-man team. If not, every time an assaulter steps out of the stack to cover angles or uncleared areas, that either leaves fewer men for room entry or members are forced to juggle between covering uncleared areas and trying to stay in the stack and flow into the room.

If that is the case, this is where gaps in security will happen. As soon as a bad guy sees the assaulter is not looking his way because he is trying to cover multiple doors or angles, that gives him a moment to pop out and spray the assault team with a burst of automatic fire from an AK.

Bumping teams up to five or six guys solves this giving you more men for room entry, ensuring you are not outgunned by multiple bad guys. It allows for extra bodies to step out of the stack and pull security locking down uncleared sectors, open doorways, and such until the team can stack up and get to them.

HALLWAYS

“Stay out of the hallway, rounds ricochet off walls and travel into you, blah blah blah….” How many times have you heard this in CQB training, that an enemy blasting rifle rounds down a hallway leads to rounds skipping off walls and turning anyone in the hallway into a bullet magnet.

Many say you should stay out of the hall and only enter as needed to get to the next room or area to clear. In my opinion, this is complete drivel.

True, when rounds hit walls, they can angle off and follow along it. But thinking the team will be able to suppress any enemy every time they need to cross or travel down the hall is flawed. In reality, by not dominating the hallway—meaning maintaining security down it—you are giving the bad guys control of the situation.

It makes no sense to fight into a hallway to then give it up by flowing the entire team out of it to take down a room every time you come back out into the hallway. You are allowing the enemy a chance to turn the doorway you are coming out of into a fatal funnel. For example, if you have a hallway with five rooms along it, that’s five times the team will have to refight to gain dominance of the hallway.

Wouldn’t it make a lot more sense to keep control of the hallway from the get-go? Why refight for the hallway after every room clearing when you can fight for it once upon entry and hold it? Instead of giving the enemy a chance to shoot at the team every time they come back out into the hallway, the team controls it. Every time a bad guy sticks his head out of a room to try to shoot the team, he’ll have a lethal surprise waiting for him.

This is not really an issue with law enforcement tactical teams going against active shooters. The best method has proven to be “direct to threat,” meaning bypass rooms and go to where the gunfire is, for there are probably only one or two threats.

But military teams cannot bypass rooms. They must execute CQB based off the worst-case scenario—multiple heavily armed combatants. Every room needs to be cleared as they come upon it. Locking down the hallway (even just one end of it) forces the enemy to expose himself to try to get at the team, turning the hallway into a bullet magnet for the bad guys. Bottom line: If you own the hall, you control the situation. Why give that advantage to the enemy?

SUMMARY

If you are training in CQB and the techniques you’re using seem to take a lot for granted, don’t be afraid to ask, “Why?” The answer may be, “This is how we have always done it” as opposed to “These methods were developed to counter current enemy techniques and tactics.” Despite being part of an assault team, you are still responsible for your own safety.

Jeff Gurwitch is a retired Special Forces Soldier who served 26 years in the United States Army (18 years with Special Forces). He served in the First Gulf War, three tours OIF, and three tours OEF. He is an avid competitive shooter, competing in USPSA, IDPA, and 3-Gun matches.