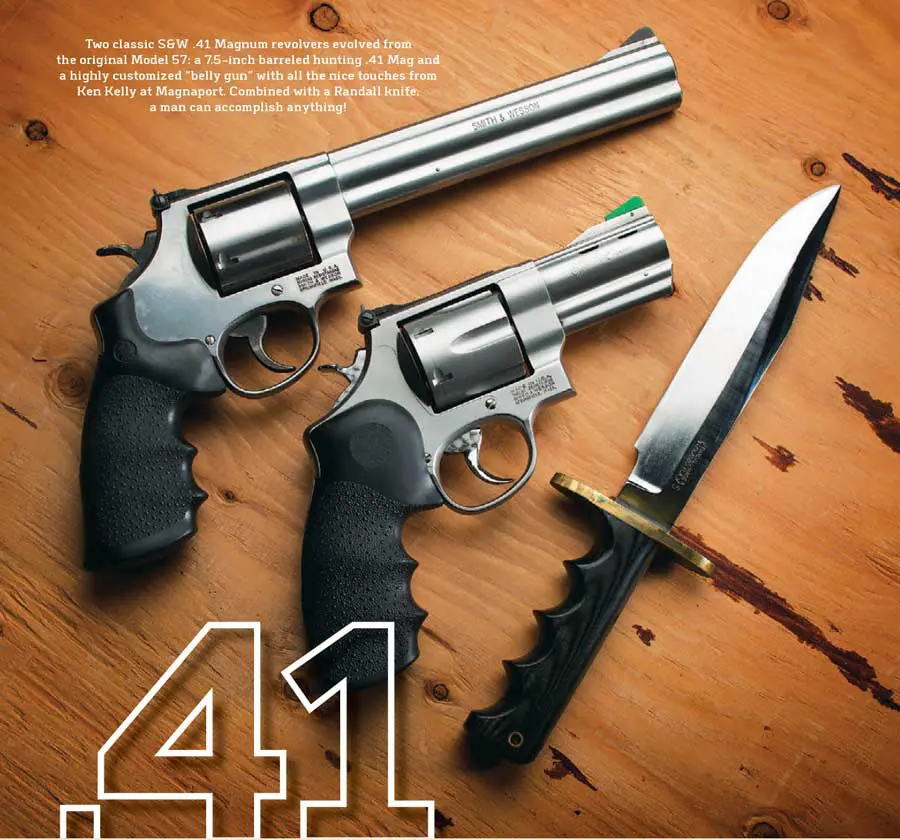

Two classic S&W .41 Magnum revolvers evolved from the original Model 57: a 7.5-inch barreled hunting .41 Mag and a highly customized “belly gun” with all the nice touches from Ken Kelly at Magnaport. Combined with a Randall knife, a man can accomplish anything!

IN 1964, the .41 Magnum was introduced to the shooting world with predictions that it was destined to be the ultimate police round.

People under the age of 40 laugh because they don’t remember a world where the police and self-defense markets weren’t totally dominated by semi-auto pistols. Older folks who remember seeing duty cops carrying revolvers tend to believe the .41 Magnum might have fulfilled its destiny had there not been a mass migration to semi-autos by police departments across America.

With the wisdom of hindsight, I’d have to challenge that belief. The .41 Magnum had several years to make its mark between its introduction in 1964 and the swell of interest in semi-autos in the late 1970s, but failed to do so. Predictions of world domination by the .41 turned into warnings of the cartridge’s projected demise.

As it turns out, the “middle Magnum” is alive and reasonably well today because it generated some devoted followers, not in the world of law enforcement, but in the outdoors market. And it achieved this following not just because it attracted some ultra-stubborn shooters prone to joining cults, but because it is a well-balanced cartridge that does almost everything a .44 Magnum does without administering the same kind of punishment to the shooter.

I’ve had a passion for handguns and handgun hunting since I was in my teens and have successfully hunted various-size game with handguns in different parts of the world. But the older I get, the less tolerant I have become of recoil abuse, and when my arthritis acts up, the .41 Magnum becomes a much more attractive option for big game than ever.

Because of my keen interest in handgun hunting, the .41 Mag revolvers I normally use are not particularly suitable for all-day carry and quick deployment.

When an opportunity to attend a three-day pistol/carbine event at Gunsite presented itself, I began rounding up the “proper” .41 Magnum hardware that a well-dressed gun writer might take to a self-defense class at the world-famous training facility.

Table of Contents

THE GUNS

Identifying and selecting the handgun candidates was easy. The first .41 Magnums from S&W were the Models 57 and 58. The Model 57 is/was the classic N-Frame with adjustable sights, large target-style wood grips, and four-inch barrel.

The Model 58 was envisioned as the “ultimate police revolver” with fixed sights, a slimmer four-inch barrel, and small wooden grips that allow easier double-action shooting, particularly for officers with smaller hands.

I also took my lightweight Model 57 (or Mountain Gun) with a skinny barrel and rubber finger-groove grips from Hogue. It’s easier to carry for extended periods of time, and the Hogue grips tend to soften the felt recoil.

The crowning glory in my armory was the Marlin 1894 lever-action carbine in .41 Magnum that had been sitting unfired in my safe for several years. It had the curved pistol-style grip and old buckhorn iron sights with a brass bead topping the front sight.

I was attending a 21st-century self-defense event at Gunsite with a 19th-century designed rifle/pistol combination shooting a 20th-century designed cartridge. Perfect!

THE AMMO

The snag was ammo. The original Remington “police load” was a 210-grain lead bullet moving at about 900 feet-per-second (fps). The theory was that the heavier bullet would penetrate deeper and the larger caliber would make bigger holes.

Keep in mind that in the 1960s, ammo companies were not yet investing big bucks in terminal ballistic performance improvements for handgun bullets. Unfortunately Remington has discontinued production of that lead bullet load, and I did not want to spend three days shooting several hundred full-strength Magnum loads.

Missouri Bullet Company sent me 500 of their 225-grain .41 Magnum Outlaw cast-lead bullets. The heavier bullet seated deeply enough in the case that loaded rounds slid smoothly from the Marlin’s magazine tube through the loading mechanism into the chamber. Seven grains of Universal Clays (my “Go To” pistol powder) produced 869 fps from my S&W Mountain Gun and 1,196 fps from the Marlin’s 20-inch barrel.

In the revolver, the load’s velocity was 30 fps slower than the original police load using a bullet 15 grains heavier. Close enough to the original specs, gentle on the old shooter (me), and totally reliable in both the Smith and Marlin.

I loaded my 500 rounds on a single-station press because I didn’t have dies for my Dillon, but as Mel Gibson said in the movie Braveheart, “That’s something we shall have to remedy!”

RELOADING BLUES

The first day on Gunsite’s handgun ranges had us doing many of the school’s standard drills at distances from three to 25 yards. Initially I was feeling a little “outgunned” given the hardware used by the rest of the class: AR-style carbines and semi-auto pistols versus my six-shot wheelgun and ten-shot lever gun. But my early thinking was based upon the number of rounds one could fire between reloads and not the number of hits achieved in the first six to ten rounds fired.

Right up until my third reload, the Mountain Gun held its own with my classmates. When doing speed reloads and replacing all six rounds using an HKS loader, I didn’t slow the class down and pretty much stayed in the fight. Once my two HKS reloaders were expended, it was a different story.

During the longer strings of fire, there were several times I found myself still reloading when the targets turned to face us or the instructor issued the “fire” command.

Tactical or partial reloads went pretty smoothly as long as I “topped off,” replacing two rounds at a time. Partial reloads of a revolver allow the muzzle to remain pointing down throughout the maneuver.

Point the revolver at the ground, push the ejector rod part way up, and then ease it back down. The unfired rounds drop back into the cylinder while (hopefully) the fired rounds remain protruding from the cylinder and can be plucked from the gun two at a time. Remove two fresh cartridges from your belt loop, pouch or pocket and insert them into the two empty chambers.

If you’re attacked partway through the reloading procedure, drop the empties or fresh rounds, close the cylinder and re-engage the threat.

It’s not nearly as fast as a semi-auto, but the good news is that there are no partially loaded magazines to deal with when the partial reload is complete.

What’s tricky is that a partial revolver reload requires considerably more dexterity and fine motor control than is needed to work magazines in and out of a semi-auto pistol. These skills are difficult to maintain in a stressful situation, so practice the maneuver.

RECOIL BLUES

By mid-afternoon I was beginning to think maybe we missed out on a good thing in the 1960s by not issuing .41 Mag revolvers to all cops. Given the ammo technology back then, my .41-caliber Mountain Gun was looking pretty good. It made big holes without depending on bullet expansion, its enhanced penetration capabilities could turn an adversary’s cover into simple concealment, and it surrendered very little in speed, placing the first six shots where I wanted them.

When I switched to the smaller Model 58, my conclusions went down the toilet. Recoil from the first four rounds caused the trigger guard to smack my knuckles so hard I was forced to bench the gun with its tiny factory grip and switch back to the Model 57 with the Hogues.

I had two more days of range time planned, much of it operating a lever-action rifle, and I needed those knuckles in reasonably good condition to make it through. I still think a .41 Mag loaded to the 900 fps level makes an excellent defensive handgun—but not in the Model 58 revolver with its tiny grips.

I don’t know anyone who originally thought the .41 Mag in a lever-action rifle would excel as a police firearm, but deep down I have a good feeling about a rifle/pistol combo that utilizes the same ammo, and the next two days working the Marlin at Gunsite reinforced that feeling.

CLOSE RANGE AND LONG RANGE

I gave up nothing to my classmates in the close-range drills where we brought the rifle up from low ready and placed one fatal shot into our assailant. Yes, when we started doing two-shot drills, there was a time lag between my first and second shots compared to the other students, but the time difference wasn’t much and my shot placement was just as good.

The Marlin’s iron sights aligned quickly on target with the brass bead visible throughout the gun’s rise to eye level. On two of Gunsite’s west-facing ranges, with the morning sun shining over my shoulder, the brass bead front sight became a ball of fire blotting out the smaller longer range targets.

Later in the day, I had no difficulties on the west-facing Scrambler with its steel targets located 80 to 120 yards downrange. Finally, on the Military Crest range with targets ranging from 180 to 280 yards, I ran out of trajectory or iron sight capability or both.

I hit some of the bad guys occasionally, but lacked consistency. I suspect a scope or higher velocity/flatter shooting load would extend the Marlin’s range, but as set up and tested, the Marlin is a 100- to 150-yard rifle using a load that is equally comfortable and effective in a handgun and carbine. That’s a pretty good urban combo.

INSET: Mountain Gun and two speed loaders carried comfortably all day in leather from Simply Rugged Holsters. An outstanding package for anyone hitting the trail.

ROLES OF THE .41 MAGNUM

So if the .41 Magnum failed in its projected role as the perfect police cartridge, why is it still with us?

As mentioned earlier, it’s a great outdoorsman’s caliber. With a slightly smaller bore size than the .44 Magnum, there is more metal around the barrel and chambers, and as some handgun silhouette shooters discovered in the 1970s, the extra metal provides enhanced gun survivability in extended shooting sessions involving maximum loads.

Several of the major manufacturers still produce versions of the original higher power .41 Magnum loads featuring a 210-grain JHP, and companies like Corbon and Buffalo Bore turn out some useful specialty loads for big-game hunting.

Using the higher-power .41 loads, no less an authority than Elmer Keith commented on the Magnum .41’s ability to shoot slightly flatter than the .44 Magnum at 100 yards. My shooting skills would not allow me to verify or contradict that opinion, but my hands will vouch for the reduced felt recoil of the smaller .41 bore with the heavy loads.

The advantage of the .44 Magnum is that you can still purchase and use the lighter .44 Special factory loads, whereas with the abandonment of the police load by Remington, the .41 Magnum requires hand-loading to tone down recoil.

Too bad the .41 Mag caliber can’t be used in cowboy action shooting since manufacturers for that market produce reduced-power loads in many of the bigger bore and centerfire handgun calibers. And without a police market to stimulate sales, there’s no incentive for major companies to spend their resources on improved .41-caliber bullet performance at low velocities.

Still, with a high-quality Smith & Wesson, Ruger, or Freedom Arms revolver chambered in .41 Magnum, there’s not much you can’t do with a handloaded hard-cast lead bullet leaving the muzzle at 900 to 1,100 feet-per-second.

GUNSITE

(928) 636-4565

www.gunsite.com

MARLIN FIREARMS

(800) 544-8892

www.marlinfirearms.com

MISSOURI BULLET COMPANY

(816) 597-3204

www.missouribullet.com

SIMPLY RUGGED HOLSTERS

(928) 227-0432

www.simplyrugged.com

SMITH & WESSON

(800) 331-0852

www.smith-wesson.com

STURM, RUGER & CO., INC.

(203) 259-7843

www.ruger.com