At the 2014 SHOT Show, Smith & Wesson introduced a new revolver—the Model 69. The 69 is an L-Frame five-shot stainless steel .44 Magnum. Did you catch that? An L-Frame .44 Magnum five-shooter?

Those three things do not seem to go naturally together. With all the fanfare over better-publicized releases from SHOT, most shooters didn’t even catch the 69. But I have a soft spot for revolvers, particularly working ones, so I anxiously grabbed one of the new .44s to test.

The L-Frame is best known as the in-between from the K and N that answered the problem of K-Frames struggling to live up to high-volume .357 Magnum shooting. The L-Frame 686s were the hot tactical trend in some regions right before service autos supplanted the wheelgun.

Table of Contents

OUNCES MAKE POUNDS

My first .44 Magnum was a Ruger Bisley, heavily influenced by Elmer Keith’s No. 5 and the writings of Ross Seyfried in 1980s Guns & Ammo articles. I was working on a cattle ranch in bear country at the time and, although the Bisley was a phenomenal shooter, the 50-ounce, 7.5-inch barreled single-action was not particularly useful as a carry piece. It got carried very little and was replaced by a Model 15 K-Frame .38 as a working gun around the ranch.

The .38 Special bullets weren’t impressive even on medium varmints and luckily never needed to be used on anything bigger. At the time, the Model 29 N-Frame Smith .44 was far out of my price bracket, the 29 always having a premium reputation and after Dirty Harry trading higher than comparable handguns.

Smith & Wesson has responded several times to the utilitarian needs of hikers, fishermen, and outdoorsmen who feel a need for .44 Magnum ballistics in a carry-friendly platform. The 1990s-era Mountain Guns are examples, and the most noteworthy was the scandium-alloy N-Frame 329 at 25 ounces.

The 329 is known just as much for its intimidating recoil as its remarkable lightness. The 69 dresses out at 37 ounces, aiming to hit the sweet spot of easy routine belt carry and enough weight to counter recoil so the shooter isn’t afraid to shoot the piece.

As context, consider some “comps” in the neighborhood. N-Frame .44s weigh about 42 ounces. The classic 1911 .45 auto typically runs 39 ounces. The Colt Single Action Army, long carried by cowboys, runs 36 for the 4¾-inch barrel for .45 Colt standard-pressure ballistics.

On the other end, the Glock 20 in 10mm is gaining popularity as a woods gun and is 30 ounces empty, but quickly adds weight with 15 rounds on board for a total of 40 ounces.

I think there is a distinct crossover point at about 40 ounces where many shooters lose interest in routine carry. Not to say there aren’t plenty who will carry much more weight without complaint, because dedicated folks have put many miles on the heavy N-Frames or even larger handguns.

But for the masses, a handgun in the mid 30-ounce range is more attractive and useful than the 40 plus. Hence the Model 69. To put it in perspective, the five-ounce weight difference between the Smith 69 and 29 equals a Leatherman tool.

PARTICULARS

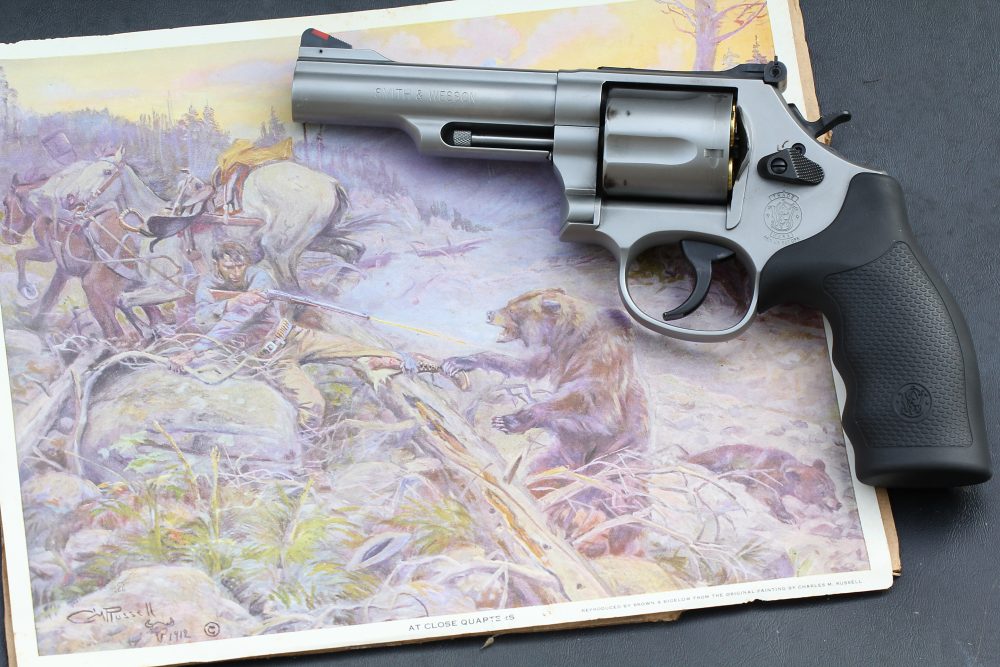

The new .44 is a stainless steel weapon with contrasting black screws and controls. It’s a striking handgun, and the utilitarian brushed finish has grown on me. The rib down the barrel sleeve is serrated and the sights are the familiar S&W adjustable rear with red insert ramped front.

The Model 69 is rollmarked “Combat Magnum,” a somewhat curious designation for a five-shot .44 Magnum, but it does look good on the barrel and has a ring to it.

The Smith engineers managed to get .44 Magnum energy into a smaller frame by dropping the capacity to five so the cylinder of .44s could fit into the frame window. They then added a ball detent to the front to provide additional locking against the higher pressures.

Whether the sixth round matters is a personal matter. It is a mental hurdle for some. I confess that I kind of wish it had the sixth round, but can’t say it would matter in a trail application.

The trigger breaks at 4.5 pounds in single-action. The numbers don’t express the feel; incredibly crisp and beyond any criticism from this end. I don’t recall shooting a full-size S&W revolver that had a poor single-action trigger pull, but this one was as close to ideal as I could have spec’d. Not too light, just a slight whisper of movement under resistance and then boom!

There is a noticeable weight to thumbcocking the hammer, requiring a smidge more effort than you might expect at first, but no real bother. The hammer has deep, sharp serrations on a smallish ledge and the trigger face is smooth.

The double-action trigger dropped the hammer at about 11 pounds of pressure, relatively smooth with a hint of stacking toward the last third. It was in the low range of pretty good/good enough and would cause some to consider some action work if DA usage was the main consideration.

The stocks on the round butt frame are a relatively new Smith offering and seem to fall between classic round and square butt profiles. The stocks offer mild finger grooves and wrap around the tang to take some of the bite out of recoil. The molded-in traction works well, providing good resistance in a sweaty grasp but allowing the hand to reposition quickly and not abrading with heavy loads. Appearance and fit are both highly personal, but I’m leaving these alone. They work exceptionally well in my hand.

Balance is subjective as well. The big N-Frame .44s, with their longer “horse pistol” barrels, seem to balance much better for me than the four-inch working guns. However, the 4¼-inch barrel on the 69 seems to hang right on target, the sights lining up with just enough weight in the handgun to steady the piece as the trigger is cycled.

In comparison, the lighter scandium 329 .44 and even lighter caliber K-Frames can be so light that the pressure of the double-action stroke can get a little shaky in the hands and transmit to the sights. The 69’s excellent balance is a defining feature: heavy enough to be stable and light enough to handle lively.

TOUCHING IT OFF

One of the good things about the .44 Magnum is the range of loads available. I started the 69 off with some defensive .44 Special loads. Recoil was a total non-event with the 180-grain JHPs and allowed fast DA work.

Stepping down another level, I tried some cowboy-action loads of 200-grain lead bullets at about 750 feet-per-second (fps). This was a distinctly “pleasant” load that almost makes you forget the ballistics are a close match to the frontier-popular .41 Long Colt—a load once favored for its effectiveness without excess recoil or overpenetration. In the Model 69, the cowboy loads could be fired by nearly anyone, regardless of sensitivity.

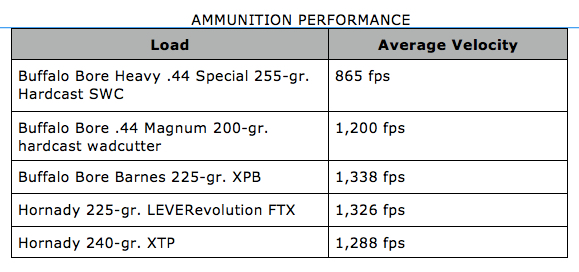

Moving up to loads near the mid-point of the .44 spectrum, I tried two Buffalo Bore rounds. The first was a heavy .44 Special 255-grain Keith-style semiwadcutter at 865 fps. The second was a reduced-recoil Magnum load featuring a hard-cast 200-grain full wadcutter at 1,200 fps.

Both of these would be manageable by most shooters, definitely torquing the wrist as the bullet leaves the muzzle, but not at a flinch-inducing level. Either load should penetrate deeply and likely through most lower 48 problems. They seemed pretty well matched as general-purpose ammo selections to the lighter weight L-Frame.

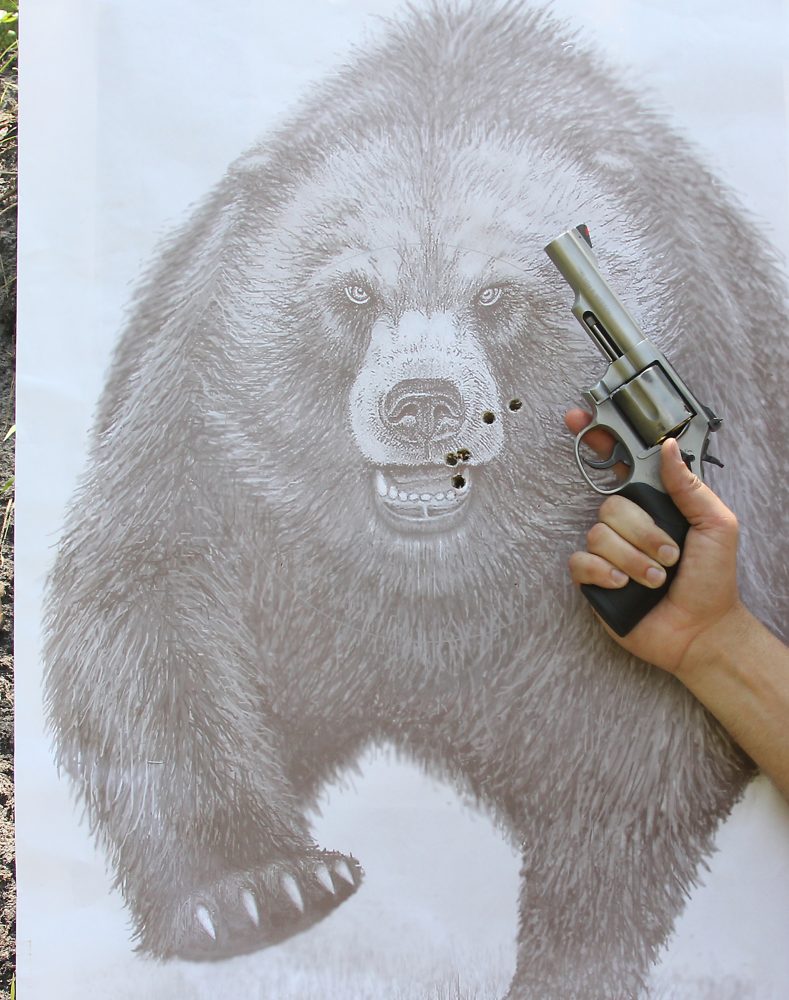

In rapid-fire against an Alaskan State Parks charging brown bear target at ten yards, the two loads were both controllable, with follow-up shots breaking at half- to three-quarter-second intervals.

Moving up the recoil ladder, I shot the Combat Magnum with two 225-grain Magnum loads, the Hornady LEVERevolution FTX at 1,326 fps and Buffalo Bore Barnes solid copper XPB at 1,338 fps as chrono’d in the 69. Both recoiled comparably and significantly. Both loads were controllable but at the upper end of what many non-big bore enthusiasts would shoot routinely.

Both bullets are current technology purpose-built for controlled expansion in hunting big game. The Hornady looks unusual, with its pointed polymer spire designed to flatten the ballistic curve and function through the tubular magazine of lever-action carbines.

The Barnes load is visually striking as well, with a gaping hollow point, the all-copper bullet designed to spread petals to significant expanded diameter but leaving enough space between them to drive to deep penetration. On the 10-yard bear charge target, they were tough to hang onto in a rapid-fire sense, with muzzle rise and torque slowing recovery.

At traditional full-house .44 level, I fired the Hornady 240-grain XTP, which clocked a little faster than one might expect from a short barrel, stepping out at 1,288 fps on average. The first of the rounds I fired was at an indoor range, and it was pretty close to an emotional event.

The blast and recoil move close to the edge between work and fun, and would discourage many shooters from any—or certainly much—practice. Outdoors it wasn’t as noticeable. The recoil level is not painful, thanks to the excellent grips, but it is pronounced. The bear drill showed me I would need a lot more practice to be able to control that much energy in a rapid-fire string. Each shot broke my grip and turned into a rapid string of regrasp/reacquire/fire.

For a hunting application, where the first shot is the main concern, the XTP is perfectly viable out of the 69. Some shooters might prefer the extra horsepower to follow-up speed in a bear gun.

There are “hot” .44 Magnum loads that crank out even more energy, but I don’t know that they have much application in this belt-gun platform. I’m in no hurry to try them.

Overall the L-Frame is not a “shoot only in case of emergency” .44. I put 90 rounds through it in one session and had no major complaints or lingering flinch. The next day I had some tenderness in the web of my palm and a little soreness in the wrist from all the torque. That wrist has an old martial arts injury, so even that may not apply to others.

ACCURACY

Many who purchase the .44 Combat Magnum will likely do so with a notion of it being a hunting-ready backup. In this role, accuracy matters significantly more than “get the bear off me” mode. As mentioned, the balance of the 69 is very, very good, and the single-action trigger on the test gun was exceptional.

This was the first of the Smiths with the two-piece barrel that I have tested, and the results showed the system to flat-out work in the accuracy department. I don’t have a knack for bench shooting handguns, so I shot the 69 braced in field positions to get a feel for the potential. While zeroing the sights, three of the Hornady 240-grain XTPs went into a single ragged .7-inch hole at 25 yards. That’ll do!

Braced over a truck bed, the Smith & Wesson poked four of the Buffalo Bore Wadcutters into 1.2 inches, with a called flyer opening the group to a still respectable 1.9 inches.

I had no issues ringing an eight-inch steel swinger at 40+ yards from standing with the .44 from both single- and double-action. Backing off to 60 yards, I sat down with my back braced and shot the 240-grain XTPs at the target. The five-shot group measured four inches, which translates to 1.66 inches at 25 yards. This particular 69 is a shooter.

MADE FOR CARRY

In the interest of full disclosure, after a couple hundred rounds in and who knows how many dry-fire cycles, I noticed the Smith had begun to lose timing. As the hammer was cocked slowly, the cylinder would occasionally not advance the next round all the way into alignment.

This was a disappointment, but Smith & Wesson has one of the best warranties in the business and promptly sent a return label and replaced the hand and the extractor. The revolver is fine now and being used for another project I’m shooting on.

This revolver is meant to carry. I’m going to enjoy finding the perfect holster for it. The extra quarter inch of barrel means the 69 may not nestle all the way into some four-inch scabbards in the holster bin. I modified two to fit while looking for one that suits the new .44. The right holster will add to the convenience of the trim L-Frame, while the wrong one would negate the advantage.

I think that overall the designers hit the sweet spot they were looking for in balancing size/weight and utility. The Model 69 hits the mark for a belt gun if the shooter is willing to forgo the sixth round.

Better yet, in my region the 69 is selling for substantially less new than well-used Model 29s.

SOURCES

Smith & Wesson

(800) 331-0852

www.smith-wesson.com

Buffalo Bore

(406) 745-2666

www.buffalobore.com

Hornady Mfg. Co.

(800) 338-3220

www.hornady.com