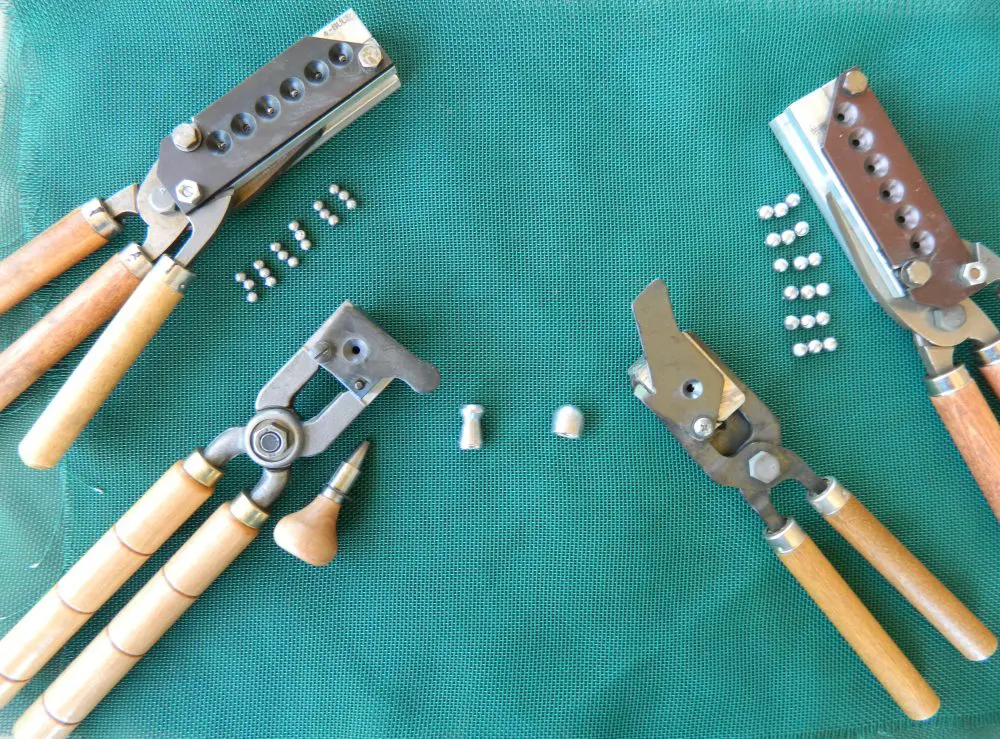

Molds for casting buckshot and slugs (clockwise from upper left): Lee 18-cavity #4 buck, Lee 18-cavity 00 Buck, Lee one-ounce slug, Lyman 20-gauge sabot slug.

Only a small percentage of the millions of shooters across the country reload their own ammunition. Among those who do reload, not many cast or swage their own bullets. Comparatively speaking, folks who reload shotshells are few and far between. I’m one of the rare birds who fall into all three categories: loading metallic shells, casting/swaging my own projectiles, and loading shotgun shells.

The main reason not many folks load shotshells is understandable. When bird season rolls around in the fall, many stores that carry ammunition sell birdshot for less than it costs to reload. Birdshot is great for, well, bird hunting. The small shot is also useful on clay pigeons, for fam fire, and in courses where learning how to run a shotgun is the primary goal, with less recoil than slugs or buck. But when it comes to stopping a determined assault against a two-legged predator, birdshot is not the load of choice.

Slugs and buckshot normally retain fairly high prices throughout the year. I have seen 12-gauge slugs go for almost $15 for a five pack (three bucks each). Due to supply and demand, one retailer sells 20-gauge slugs for $22 for a box of five shells!

Depending on the equipment used, getting into reloading buckshot and slugs for a shotgun can actually be less expensive than many metallic cartridge systems. The first thing you should obtain is a good shotshell manual. I recommend Lyman’s Shotshell Reloading Handbook, 5th Edition.

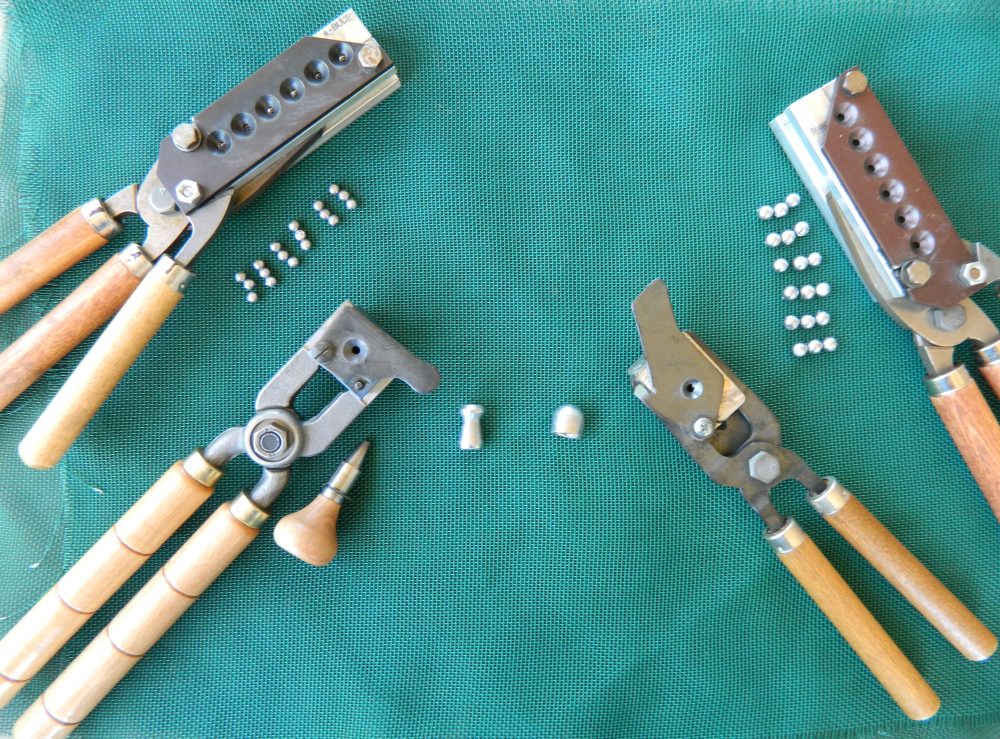

Buckshot pellets come out of the mold attached with a small sprue and must be cut apart.

Unlike metallic loads, shotshell reloading is a bit more specific. As long as the powder charge is correct with a certain weight bullet, cases and primers can pretty much be interchanged with metallic loads.

But with shotshells, attention must be paid to what hull (case) is used, as well as the primer, powder charge, shot wad, buffering material (if used) and, of course, the powder charge weight. Any deviation can result in a load with possibly dangerous pressures. Once again, use a reputable manual. Home-brewed loads from the Errornet should be avoided like the plague.

I’ve loaded 12 gauge on a legacy Lee Load-All press for many years and recently started loading 20 gauge on the improved Load-All II. Suggested retail price for the Load-All II is around $75, but it can be found at many sporting goods stores for around $55. A conversion kit for other gauges costs about $25, so for less than a C note, you have the necessary equipment to load shells. Once set up, I have no problem loading 100 or more shells an hour.

Good example of a mold that is not hot enough—wrinkles in pellets and not a complete fill of the mold cavity. Wrinkles can also be reduced by adding a small amount of wheel weight alloy.

Table of Contents

A WORD ON CASES

Most folks relate “high brass” cases with more power, and “low brass” with light field loads. There was a time when this was true, and it’s a holdover from when shotgun hulls were made of paper and there was a possibility of the powder burning through the case with heavy loads, so a high brass head was used to minimize the chance of a “burn through.”

Today, it is more of a marketing ploy than a necessity. In fact, some cases—Active brand comes to mind—have been made with no brass or metal on the head at all. Examine each hull carefully and, if any exhibits cracks at the end, discard it, as it will not end up with a good crimp.

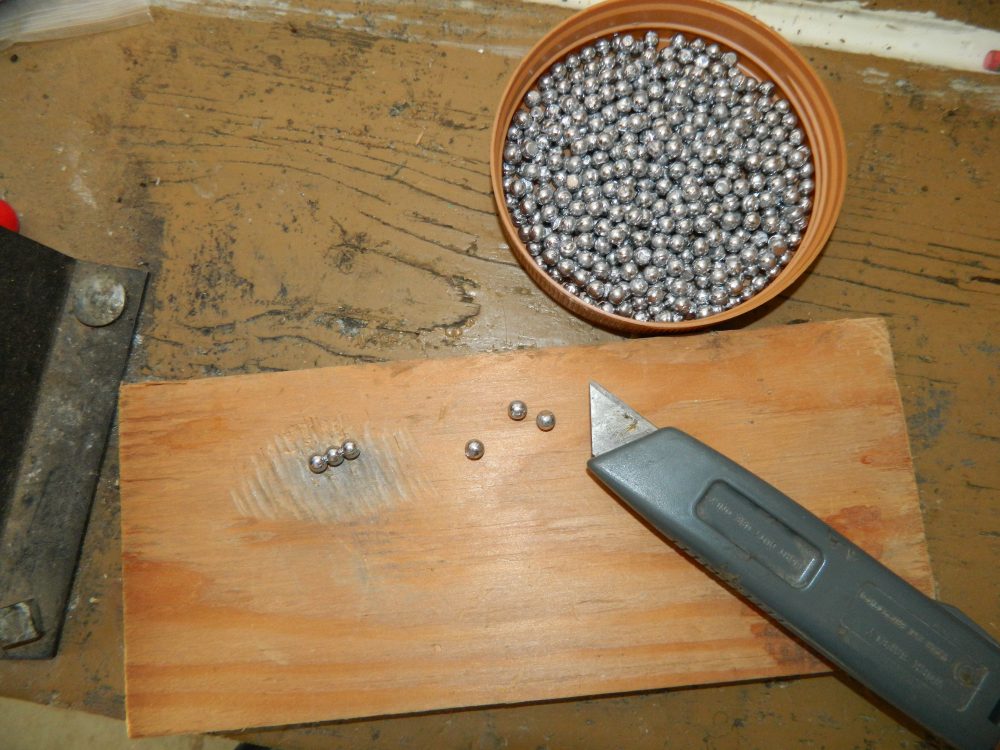

A few hours casting yields enough buckshot and slugs for a lot of practice.

OTHER COMPONENTS

Even for casual practice, you should strive for good patterns/groups. Harder buckshot will usually result in tighter patterns, as the shot will not deform as much as it travels down the barrel. Mold manufacturers, however, advise to use pure lead.

A good buffer material will also help produce better, more consistent patterns, especially when using soft or semi-soft lead. While some people have reported good results using cornmeal, I prefer a purpose-made commercial buffer material. My first choice with buckshot is Ballistic Products BPI Mix #47.

A cardboard wad called an overshot card serves two purposes. The first is a flatter, tighter crimp. The second is to make sure the buffer material does not leak out. As mentioned earlier, any change in components can result in unsafe pressure spikes, so don’t use buffering material or overshot cards unless the load specifically calls for it.

Slug molds especially like to run much hotter than usual. On the left is a slug from a very hot alloy and mold. On the right is a slug cast at the same temperature author casts pistol bullets at.

PREMADE OR HOMEMADE

For the projectiles, you have two choices: buy premade slugs and buck or cast your own. Buying premade gives you the choice of a larger variety of slug type and buckshot, including hard shot and even copper clad buck. A good source of buckshot and slugs, as well as hulls and wads, is Ballistic Products.

CASTING SLUGS AND BUCKSHOT

Casting your own buckshot and slugs results in savings but requires additional initial expenditure. The amount you save, as with all reloading endeavors, will depend on how much you shoot. I shoot a lot of shotgun, and so rather than go with top-of-the-line buck and slugs, I cast my own for practice ammo. (I rely on Hornady or Federal shotgun ammo for “social” purposes.)

Due to the sprue plate cutting off the sprue from the casting, the top pellet from a buckshot mold will be flat rather than round and will not fly as true as a round pellet. If you want the tightest pattern possible, this pellet can be cut off and put back in the lead pot. But it is suitable for practice loads.

Slugs

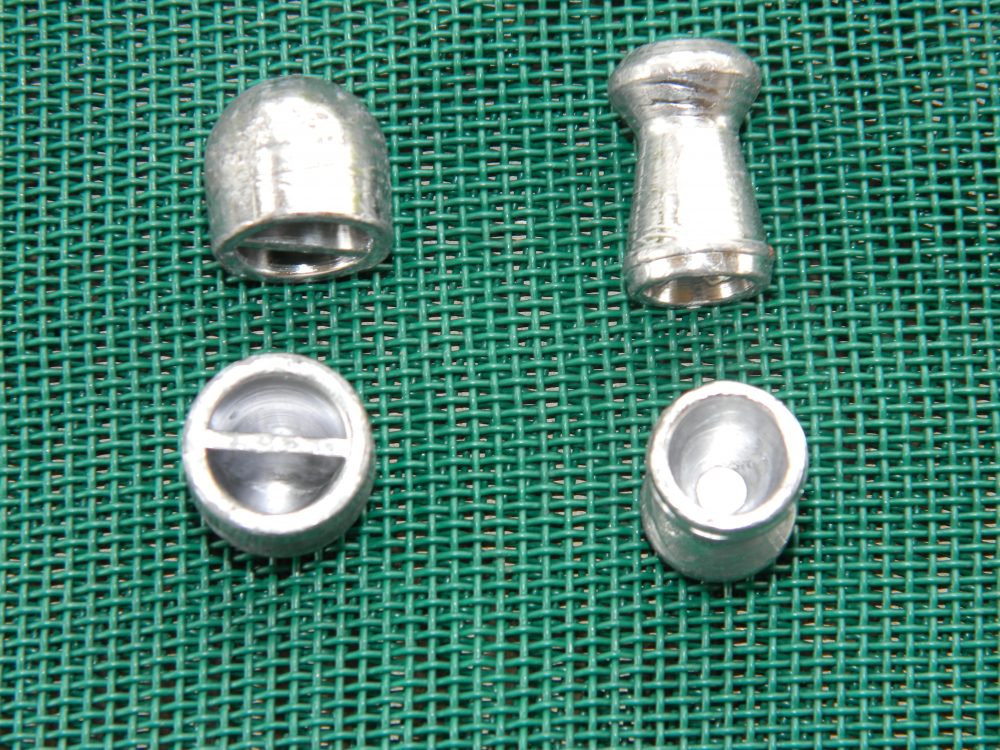

Slug molds run from $30 to $90, depending on which molds are used. My most expensive mold is a Lyman 20-gauge sabot mold that throws a 350-grain slug. My least expensive is a Lee 12-gauge, one-ounce Foster-type slug mold. Both these molds use standard wads and use a standard star crimp, so they don’t require a special roll crimp tool.

Casting slugs from the Lee slug mold is a bit different than other bullets, in that it has to run a lot hotter to drop projectiles without wrinkles. This is likely due to the Drive Key design in the Lee slug.

The Lyman sabot mold turns out good slugs at a more normal temperature, but since the sabot has a hollow base, a plug must be inserted every time before the sabot is cast. A little more time consuming, but a few hours will yield enough sabots for a lot of shooting.

Adding a small amount of wheel weight alloy, no more than 1:10 ratio, helps the molds fill out better with fewer wrinkles. It will also make the slugs slightly harder, for better penetration.

Factory slug loads use a roll crimp, allowing them to be identified both tactilely and visually as a slug. You don’t want to launch a slug when you intended to fire buckshot and vice versa, so loads should be marked with a permanent marker and kept separate.

Buckshot

While it is possible to cast buckshot with inexpensive single- or double-cavity molds, these molds are primarily designed to make sinkers for fishing and are not very efficient for casting a large amount of buckshot. I use 18-cavity Lee Buckshot molds. When casting 00, each filling is equal to two shotshells. These molds cost around $50 to $65 each, depending on the source.

Although the Lee molds have six cavities that each throw three pieces of shot, each piece comes out of the mold as three balls connected with a very thin sprue, requiring them to be cut apart. A utility knife works well for separating the pieces of shot. Splitting the shot apart is also a good time to cull any pieces that have not fully formed. Once the mold is up to temperature, I have about a 90% full fill rate.

As the sprue plate cuts off the sprue from the casting, the top piece of buckshot will be flat. This is more pronounced as the size of buckshot is decreased. The flat end will prevent it from flying as straight as a round ball.

If the best possible pattern is your goal, the flattened piece of buck can be culled while cutting them apart and remolded later. But culling them will reduce your buckshot production by a third. At normal buckshot ranges, I have found it does not make that much of a difference, and I can live with a flyer or two in practice.

Profile and interior views of Lyman 20-gauge sabot and Lee one-ounce slugs.

IS IT WORTH THE TROUBLE?

Only you can decide if reloading shotgun shells, especially slugs and buckshot, is worth the expense, labor and time. As mentioned earlier, it largely depends on how much you shoot.

Ringing a steel plate at 75 yards with a slug gives a certain amount of gratification—even more so when your wallet is not feeling lighter with each shot.

SOURCES:

Ballistic Products

(888) 273-5623

www.ballisticproducts.com

Lee Precision

(262) 673-3075

www.leeprecision.com

Lyman Products

(800) 225-9626

www.lymanproducts.com