AR-type .22 rimfire conversions and trainers have flown off dealers’ shelves by the thousands, with shooters looking to mimic the appearance, form or function of their service carbines. Some of these shooters didn’t grow up on a steady regimen of rimfire shooting, while others are now shooting the .22 in volumes not encountered before. In either case, there are tips and considerations to help a shooter get more out of the rimfire trainer so that there is genuine training benefit and skills transfer back to the “big” gun.

Table of Contents

IT MAY LOOK LIKE AN AR, BUT IT AIN’T!

The beauty of the better trainers is that they do a great job of mimicking the feel and operational controls of the full-size AR. This can lead to some problems if the shooter doesn’t take into account the key differences between the rimfire and its big brother. First, rimfire ammunition is invariably dirty, with unburned powder, bullet lead and lube residue, and filler particles in many loads. Some loads are ridiculously dirty when shot in serious training quantities.

If you are in the AR camp that substitutes more lube for a cleaning regimen (yeah, me too oftentimes), this will prove incompatible with your rimfire training objectives. Because of the inherent detritus involved, it is best to stay ahead of the curve and occasionally pull a boresnake through the barrel to keep the gunk knocked out of the chamber.

Rifle/ammo/lube interactions vary, but I try to go no more than 350 rounds before cleaning. When the shooter does this, the occasional stoppage can be reduced with the same flow as a normal immediate action drill. When the chamber is 900 rounds in, tap/rack may not get the proceeding round all the way into the chamber. This is mildly significant, since the trainers are blowback operated, meaning the spring tension pushing the bolt against the breech is all the “locking” that is going on.

So, immediate action with an overly dirty chamber may occasionally work due to the variation in individual bullets, but may just as likely result in either a “dead gun” due to the bolt being out of battery, or worse, fire out of battery and result in a mild “kaboom” that will probably shear your extractor and spit some brass into you or your neighbor.

The rimfire trainer with a high-volume diet may not react positively to being lubed like an AR at a high-round-count class. The differences in how they operate internally, coupled with the “dirty-osity” of the rimfire ammo, may make lubing with a squirt bottle or needle applicator counterproductive. People tend to lube every weapon in the armory the same way, but each system has its own preferences in the lube department. In Ruger 10/22 trainers, I’ve had the most success with a drop or two of lube targeted toward the top of the bolt and guide rod as it fouls, while with the Smith & Wesson 15-22 I’ve had the best possible results with just a finger smear of Slip 2000 on the twin bars that the bolt reciprocates along, and no more.

.22s ARE FICKLE ABOUT AMMO—YOU SHOULD BE TOO

It is reasonable to expect a service carbine to run with any service-grade ammo and maintain acceptable accuracy. Once you pick up a rimfire surrogate, it isn’t. If the shooter accepts this and moves on, quality of life improves immediately.

Some rifles will outright reject certain brands and/or speeds, while others will simply reward careful selection with greater accuracy and perfect reliability. Rimfire ammunition is available in three velocity brackets, generally recognized as standard, high, and hyper velocity. I generally begin the quest with readily available bulk loads in the high-velocity bracket. If a particular rifle or conversion is disappointing in accuracy or function, I first switch brands to another high-velocity bulk load, which often solves the problem, and move as needed from there up or down in speed.

A standard-velocity round may simply lack the oomph to push the bolt back far enough to reset a conversion unit’s AR trigger group 100% of the time. Likewise, hyper-velocity stuff may get ahead of the magazine’s ability to consistently feed the next round to the bolt face. Besides speed, differences in the actual bullet profiles and minor dimensional variations can challenge best reliability.

I had completely sworn off one major maker’s common bulk ammo as an anti-gunner plot to deny semiautomatic function until learning that a trusted shooting partner found it the best load in his Glock conversion.

A word of caution is germane at this point: the nature of a rimfire round’s construction and the recent supply/demand situation have led to severe issues with rimfire ammo QC. I recently shot through a 333-round box that was replete with crooked and mangled projectiles, many of the bullets actually having missed the final forming of the ogive.

Barring unexpected ammo issues, acceptable reliability can be achieved in the better conversions and dedicated training rifles, and it is worth the effort to find the most compatible load, since immediate action techniques may not directly transfer to the rimfire trainer.

Minimizing so-called training scars is key, and simply not having to reduce stoppages is the best way to deal with dissimilar manuals of arms, as in the case of the 10/22-based platforms. I worked my way through a variety of the available bulk-pack loads until finding one that shot reliably out of all my trainers, burned pretty clean, and grouped according to my training needs. Then I embarked on the great scavenger hunt in the ammo famine of 2009 to lay in enough of that type and lot to shoot worry-free for, oh, a “few” years.

WHY DO YOU HAVE IT?

There are two primary training reasons for having a rimfire trainer: access and cost savings. Looks cool, “I just want one,” and so on are perfectly acceptable buying motivations, but from a skill perspective, the rimfire either allows a shooter to train someplace where he otherwise wouldn’t be able to or allows him to burn through ten to 12 times the repetitions of a given skill at the full-power cost of a single shot.

A city dweller who only has access to a pistol range must consider his rimfire training objectives carefully to make sure that the full range of skills is addressed, whereas a thrift-minded shooter can be more selective in drill selection, training key things centerfire and switching to subcal to reinforce or round out the rest of the drill card.

Compensate for the flinch-inducing blast and recoil. The .22 provides a great opportunity for shooters to push themselves harder for both speed and accuracy. The lack of recoil and blast allows a shooter to really focus his or her shot to get a crisp break and follow through while emphasizing “reading the dot” (or front sight) to call shots and recover to the next sight picture.

A good rule of thumb is to reduce the normal target zone at a given distance by half. This forces the shooter to tighten up and maintain an aggressive posture or use support as the position dictates, rather than allowing the dread plinking posture to hearken visions of coolers, shade trees, and tin cans. A shooter who maintains overly large targets and doesn’t challenge the performance will find a tendency for training to morph into plinking. Plinking is an established American pastime, but doesn’t translate very well to gunfighting skills.

For speed, the shooter can maintain the smaller targetry and shoot for full-caliber time limits. As an example, a shooter should be able to manage the sights, trigger and recoil well enough to keep several subcal shots in an apple-sized area in a similar time as he would be able to ride the dot into the chest area vitals of a threat. Or shoot expected target zones for a given distance and reduce the par times significantly.

There are training benefits to either approach: one emphasizes manipulating the trigger and reading the dot as rapidly as physically possible to bump the shooter’s performance up a level, while the other is a better replication of the centerfire drill. A good rimfire training regimen makes use of all compensated techniques and challenges accuracy, speed and both together to push the shooter as hard as possible. This is particularly important for access-driven subcal shooters, since they are not getting the regular sustainment on the real carbine and must not fool themselves by plinking their way through drills or practice quals, or the fighting stance will have degraded when they do have to pick up the larger carbine to fight with.

RATIO

Even with proper compensation, there is the risk of overdoing the simulation thing. I went a little overboard while focusing on drill development for the rimfires and found myself momentarily the slightest bit surprised and not managing the gun hard for the first few rounds of green tip that went downrange during a training session.

Access shooters’ situation aside, there can be too much of an otherwise good thing. There are different opinions about what percentage should be live 5.56mm. I see best results at about a three rimfire to one 5.56mm ratio, ideally in the same training session. This keeps the positions essentially the same and maximizes transfer back and forth.

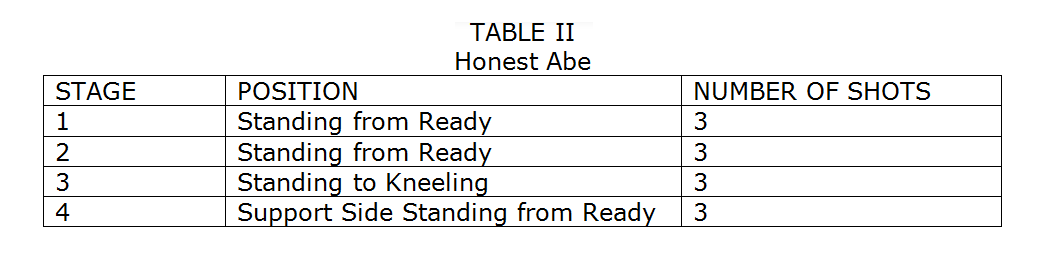

However, many shooters are using the rimfires because of the cost and availability of ammo and simply will not keep up with that ratio. For them, I recommend a drill called “Honest Abe,” which is designed to allow the shooter to train through a drill card with his or her subcal carbine and then break out the service gun and 12 rounds to finish the day. At the going rate for 5.56mm, that’s about $5 and well within the serious training student’s ability to budget.

The Abe is set up at 25 yards on an eight-inch target. The distance is intentionally longish: Shooting any closer would allow the student to mask rimfire-induced looseness that may have crept in. The shooter begins at the low ready with the centerfire carbine and puts three rounds on target for time: twice from standing, once from kneeling and a final time from support-side low ready. The goal for total aggregate time with 12 hits is 12 seconds for mission-user types. This is cooking along pretty good and requires the shooter to manage the gun with solid technique and clean presses. It is a great way to finish up the training day and leave having forced yourself to stay aggressive on the carbine.

The .22 trainer is a tremendous asset for today’s gunfighter. Each training session I find more training applications for it and can directly attribute measurable increases in overall shooting capability to the additional time spent behind it. Have a go at the drills described in the sidebar and tables and start tracking your progress.

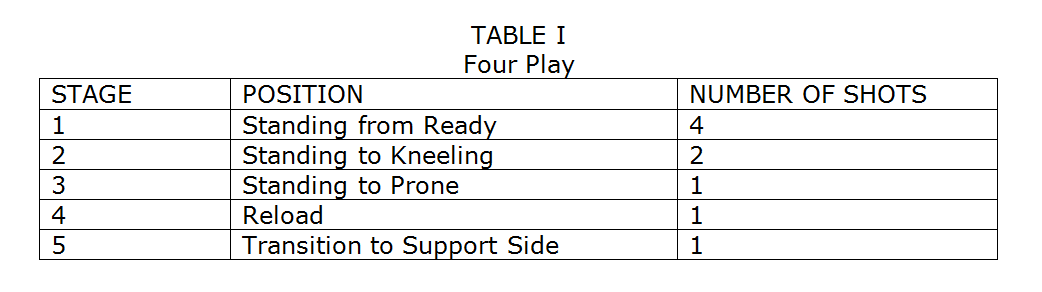

FOUR PLAY DRILL

Each stage has four strings fired at a four-inch target in a time limit of four seconds. For targets, use either a 4×6 index card folded over to make a roughly four-inch square, or if you are feeling flush, a four-inch Caldwell Orange Peel marking target. A shot timer set to par time is ideal, but four seconds is enough of an interval that a training partner with a stopwatch will suffice. The drill is designed as a 25-yard affair, but it is best that shooters start at 15 yards and “earn” their way to the 20 and then to the 25 as their skill level allows.

Stand And Deliver

The shooter begins in whichever ready position he trains to, safety on for AR conversions or dedicated trainers, off for surrogates like the Ruger 10-22. At the buzzer, simply get on the gun and fire four shots. Note any late shots and recover to the ready. Repeat for a total of four strings. The time limit, target size, and multiple shots help to force the shooter into an aggressive position that translates well to the service carbine. While a shooter could relax into plinking mode, he will probably be rewarded with misses or late hits. This stage has a total of 16 possible hits.

Take A Knee

The next stage begins at the ready and has the shooter transitioning to kneeling to fire two shots in the allotted four seconds. Any kneeling position will do, although I like to work different ones into the four strings—for example, stretch kneeling on string one, double kneel on string two, traditional kneeling on three. As with the standing portion, there is little slop in the par time, so the shooter must be aggressive in movement and shooting to make the hack.

Get Down

Stage three begins at the ready and has the shooter going to prone to fire a single shot to the four-inch bull in the four seconds allowed. The shooting is not the hard part here—the effectiveness of the drill comes in smoothing out the motions in getting to prone and behind the gun. This is one of the harder stages for some, although the hits from prone should be “gimmes.” Luckily you only have to get down and back up four times.

Feed It!

The fourth stage starts with the bolt locked back on an expended magazine, finger on trigger and safety off, just as a reload would occur in reality. At the cue, the shooter executes a reload as smoothly as possible and concludes with a shot to the four-inch mark. Note any late hits and repeat for a total of four reps. For those using conversion bolts that do not lock back, you have the option of running a speed reload and going through the motion of actuating the bolt release.

Get It Across And Continue The Fight

The final stage is a support-side transition. I like to begin with the sling on and the weapon at the hunt. When the buzzer goes off, execute a transition to the support side and smack the target. Note any late hits and repeat for the established pattern of four. The par is challenging and may be counterproductive for average shooters until the mechanics are smoothed out.

Maximum score across the course is 36 points. The drill is not particularly easy and makes the shooter work for the hits, so 32 points is the cutline for bragging rights, with the goal obviously being to max it. If the hits just aren’t in the time limit, move the targets closer in five-yard increments while maintaining the four-second par until the hits are possible for the majority of attempts.

Once the shooter is proficient with more fundamental drills, Four Play works very well as a support-side skill builder. The par is increased to five seconds to allow the shooter enough time to place the hits from the less experienced side. Aside from more advanced shooters who both set up their gear and routinely practice mirror-image reloads, most shooters are better served working through the reload stage with no time limit and simply focusing on positive control and good technique.

Four Play

All shots fired to four-inch target at 25 yards. Each stage repeated for total of four repetitions.

Honest Abe

All shots fired to eight-inch target at 25 yards.