You’re in the process of rotating your food supplies when you notice that the “Best By” date on some of the containers came and went over five months ago! If you’re like most people, your first reaction is probably to throw out any food products that appear to be out of date. After all, who wants to eat expired food? You certainly don’t want to risk getting sick, right?

As consumers, we should all be concerned with the quality, freshness and safety of the foods we consume. In that regard, many of us would not hesitate to discard any food that we suspect may be spoiled or unsafe. But is it always necessary to throw food out just because it’s past the “Best By” date? New research suggests that many food products are perfectly safe to eat even if the date may suggest otherwise.

Table of Contents

WHAT’S IN A DATE?

“Sell By,” “Use By” and “Best Before” labels are on just about everything we buy at the supermarket, but do we really understand what these dates represent? Some food experts suggest that many people don’t. These dates are not only very confusing, but they also don’t actually mean what most of us think they mean. Confused yet? Don’t feel bad, you’re not alone.

It’s not uncommon for people to throw out food solely on the basis of the date. Some of us take that process even further and throw out food that is nearing the expiration date “just in case.” Are we making the best use of our grocery budgets when we discard food in this manner? And more importantly, do we really need to throw away food just because it has reached one of these ambiguous dates?

FOOD DATE LABELS

The majority of the food date labeling in the U.S. is voluntary. Contrary to popular belief, the only food products required by federal law to be labeled with an expiration date are infant formula and baby food—that’s it. So if it’s not mandatory, why have any dates at all? There are some state-level regulations, but they lack uniformity and can vary greatly from state to state. With all the confusion and misinterpretation, it’s not surprising that consumers often choose to err on the side of caution and discard out-of-date products.

In September 2013, a joint report was issued by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic. As it turns out, just about everything we thought we knew about food expiration dates is wrong.

According to this report, Americans are throwing out perfectly good food and wasting lots of money due to a mistaken belief that once “the date” has been reached, the subject food is somehow unsafe to consume. The report further states that in actuality, food expiration dates are only suggestions by the manufacturer for when the food is at its peak freshness and quality, not when it’s unsafe to eat.

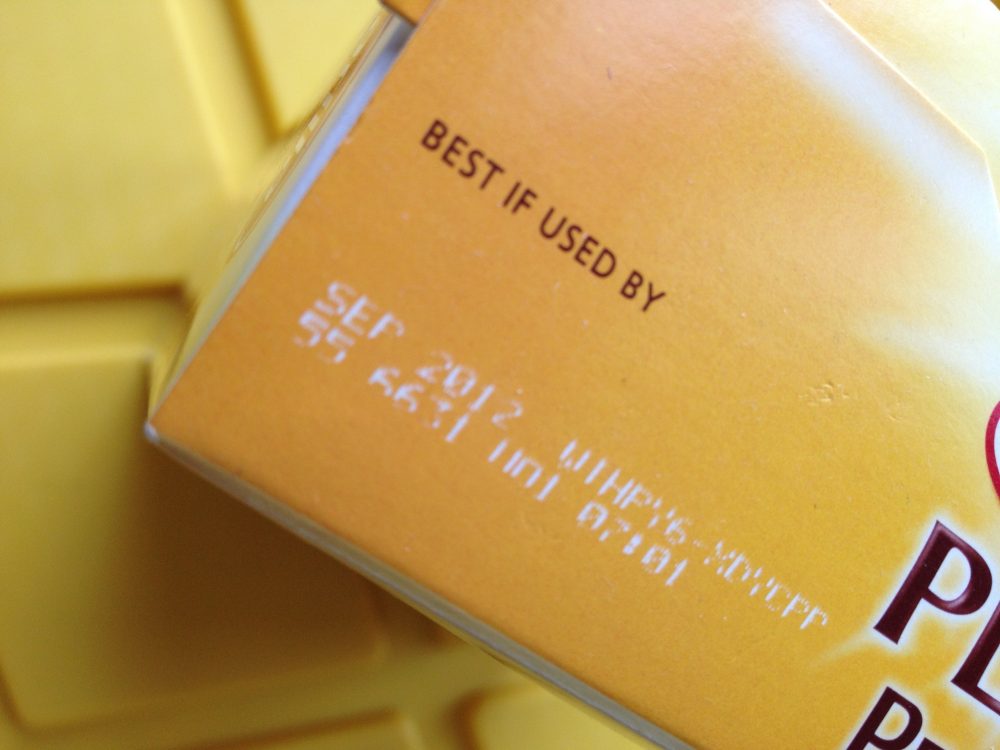

On many products, the “Best By” date is imprinted near the top.

EXPIRATION DATES AND PREPPING

For many of us, our stored food supplies make up a critical part of our preparedness plan. Only water and security are generally considered more important. When preparing for the unexpected, we often devote a considerable amount of money, time and effort to food, with freshness and nutritional quality certainly top priorities.

After all, it would be of little value to go through the time-consuming and often expensive effort of building up an emergency food supply only to discover, usually at the worst possible moment, that the stored food is unsafe to eat. It defeats the purpose entirely if the food we store is unusable for any reason.

Food in cans, jars and other containers makes up a large portion of most preparedness food stores. Making the most of our supplies requires knowing how to store, rotate and manage our inventory in the most efficient and effective way possible. Used correctly, food labeling dates can be important tools.

The following are some of the most commonly used date labeling terms and what they mean, though the actual meaning will vary depending on the manufacturer and the state in which the product is being sold.

Store canned goods in a cool, dry place away from heat, moisture and direct sunlight. Rotate all food supplies on a regular basis. Use a marker to rewrite the “Best By” year on cans for easy reference.

SELL BY

This date usually lets the store know how long they should keep the product on their shelves. This designation does not mean that the product will be unsafe to eat or spoiled the day after the “Sell By” date. The labeled date is a tool to help the retailer rotate their displays, and represents the date that the product will probably be at its highest level of freshness, but it will still be edible for some time after the “Sell By” date.

USE BY

This is the manufacturer’s recommended date of use, if the consumer wishes to enjoy the product while it’s at the peak of freshness. This date is chosen by the manufacturer and may differ significantly for similar products made by different manufacturers.

But for some products, you’ll need to break out the magnifying glass to read the date.

BEST BEFORE

This date refers only to quality. It is not an indicator of safety. It is a recommended date for the best quality and flavor.

Knowing what these dates mean and how to use them can be very helpful when managing both everyday and long-term food supplies.

ROTATION

The keys to successful food management are proper storage and ongoing rotation. One strategy is to buy and store what you eat on a regular basis. This practice allows you to always have the freshest possible food products. As you use your stores, replace them with new products and rotate the remaining stock—use the oldest first and stock the newest for later. As you rotate your supplies, refer to the food label dates.

Many retailers use these dates as a tool to help them display and rotate their inventory. If you have food products with older dates, use those products sooner rather than later. Products with more current dates should be rotated toward the back and moved forward as you buy new supplies.

Proper food storage is important. Store all food products in a cool, clean, dry place away from heat, moisture and direct sunlight. A thermometer and humidity gauge will make it easier to monitor storage conditions. Between 50 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit is a good temperature range. Temperatures over 100 degrees are harmful to canned goods and will drastically reduce shelf life.

IS IT SAFE?

Regardless of the food labeling dates, what they mean, or how they should be used, there are other factors to consider in determining if a food is spoiled or unsafe to eat.

For example, to help reduce the chances of getting sick from eating canned or jarred foods that have spoiled, always inspect the can/jar and its contents before consuming. Food poisoning can be a very serious problem during normal times, even with proper medical attention. During a disaster, food poisoning and its resultant complications can easily kill you.

If you see any of the indicators listed below, the food should be treated as suspect and immediately discarded. If in doubt, throw it out!

- If the can or jar lid shows signs of rust, corrosion or damage to the seal.

- A can that is dented, deformed and/or bloated.

- A bulging can or lid.

- Food that is discolored, mushy, moldy or smells foul.

- The can or jar squirts liquid or foam when opened.

Make a visual inspection of all cans, jars and other food containers. Any cans or jars fitting the descriptions above are bad news, and their contents should not be consumed. Dump them and move on—at this point it doesn’t matter what the date is.

BOTULISM

Botulism is a rare but potentially fatal illness. Some 100 cases of it occur in the U.S. each year. Botulism is caused by a toxin produced by the bacteria Clostridium botulinum, considered one of the most potent and lethal substances known. The bacterial spores are odorless and can’t be seen by the naked eye. Food-borne botulism is caused by eating food that contains the toxin.

Symptoms usually start to appear between 12 to 36 hours after eating the contaminated food. Early symptoms include fatigue and muscle weakness, followed by double vision, dry mouth, difficulty speaking and swallowing, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal swelling.

Although botulism poisoning from commercially canned food is uncommon in the U.S., cases do occur. Food cans with dents on the seams, or where the side of the can meets the end, should be considered suspect and discarded.

A compromised can allows the growth of the micro-organism that causes botulism. Inspect all cans: feel for dents, and visually inspect for rust, punctures, swelling or bulging. Swelling usually occurs due to gas production from bacterial growth inside the can. Avoid all swollen or bulging cans.

Never taste suspect food to determine if it’s safe. Even just a small amount of this toxin can be fatal. Botulism is a medical emergency. If you have symptoms, seek immediate medical attention.

CONCLUSIONS

Food label dates are often confusing and may not mean what you think they mean, but when used correctly, they can be an important tool in managing your food supplies.

Surviving a natural or manmade disaster requires solid planning and practical preparations. Food is one of the most critical components. Managing and maintaining your food supplies and knowing how to use those stored products safely and efficiently are key to making the most of your efforts.

Planning, rotation, proper food storage and careful inspection of food product containers can help reduce the chances of contracting food-borne illness, and maximize your food storage efforts.

HOW LONG IS TOO LONG?

If the date labels are not an indicator of food safety—and absent any uniform guidelines or standards, each manufacturer is free to use label dates as they see fit—how does the average consumer know if a food product is safe to eat or not? Is it good until a month after the sell-by date? A year after? Five years? Ten? How do we know?

With perishable food such as produce and dairy products, we don’t even need date labels. Simple visual and/or olfactory inspection tells us immediately if the food has gone bad and should not be eaten. But our survival food stores are not made up of these perishable items. Instead they contain packaged food that doesn’t give so many clues whether it is safe to eat or not.

Until there is some sort of mandated national labeling regime with clear uniform standards, most consumers will be well served by employing good old common sense and erring on the side of caution when it comes to food safety. Here are some tips to help in this process.

When in doubt, throw it out. While it hurts to throw away food, it will hurt a lot more to become ill. Look for signs of spoilage, contamination, and damage to the container. If you’re not sure, don’t take any chances.

Storage conditions matter. Storage conditions at the manufacturing plant, warehouse, in transit and at your home will also determine how long a product will remain safe to eat. Temperature, humidity, and pests all matter. For example, if food products are stored in high heat (100+degrees), dates become meaningless and food can go bad long before the label date.

What you don’t know can hurt you. Having no practical way of knowing how an item was stored prior to purchase, consumers can still protect themselves, to a reasonable extent, by shopping at reputable retailers and avoiding foods from unknown sources no matter how good a deal that box of dented cans may seem at the time.

Rotate, rotate, rotate. Ongoing rotation remains one of the best ways to protect yourself from spoiled food. Frequent inspection of your food stores for the relevant risk factors (damage to containers, leaking cans, etc) will help you identify suspect products and keep your inventory current.

Richard Duarte is a practicing attorney and currently teaches and consults in the areas of urban survival planning and preparation. He is the author of Surviving Doomsday: A Guide for Surviving an Urban Disaster. For the latest news and updates, connect with Richard on www.survivingdoomsdaythebook.com