What is best for the “Grandpa’s-gun-somewhere-in-a-drawer-just-in-case” crowd is not necessarily what’s best for an entry team. Different missions require different levels of capability, which drives different training and resources.

There are many healthy debates in the training community, some of them perennial favorites such as caliber wars, the role of unsighted fire, the best stance, etc. However, these discussions are often conducted without the proper framework. The simple question of “For whom?” is rarely properly addressed.

In one corner, the double-action-only service auto proponent is picturing a firing line full of gun-belted simpletons, while his sparring partner is passionately talking past him while describing a hostage rescue team stacked up with cocked-and-locked 1911s in hand. There is definitely a benefit to laying out some broad groups of armed personnel and framing discussion, evaluation and decisions properly within those groups.

In the past, there have been anywhere between three (Marksman, Sharpshooter, Expert) and seven (Novice, D, C, B, & A Class, Master and Grand Master) categories used to capture skill level. This is generally tied to a certain qualification score or competitive ranking within a shooting discipline. This categorization is far too narrow to be useful. The result has often been trainers either mentally lumping everyone into the least common denominator or assuming the “ideal” geared around the top tier of performers. Neither approach works out any better than would teaching all average math students as if they were either learning disabled or calculus whizzes.

There are four broad categories that can be established based upon the users’ mission, capability and experience. The accompanying tables define these groups by these attributes. Undoubtedly there are exceptions, but these are broad averages that attempt to capture useful distinguishing features.

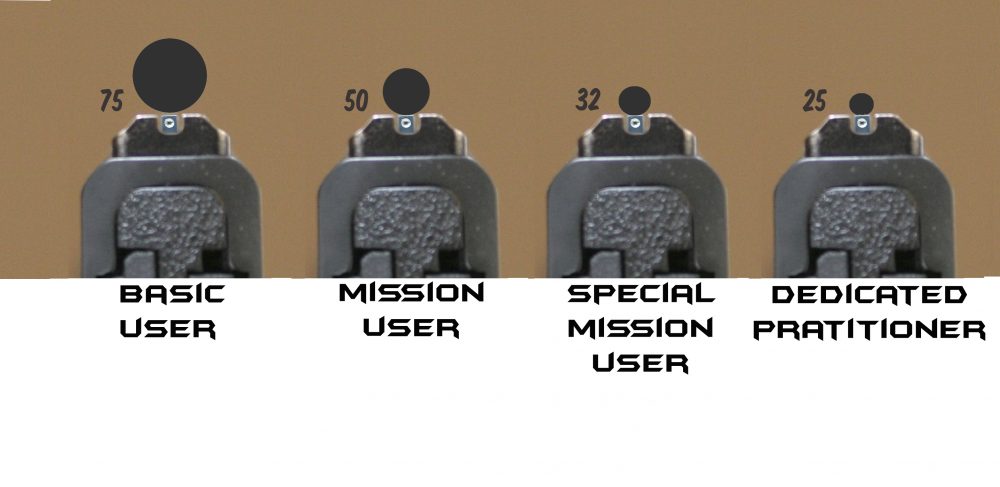

Representative sight pictures showing approximate level of accuracy (shown in MOA) that can be expected from each user group. This represents capability under moderate stress and what shooter can produce on demand—not hit on occasion or at best. Warren Tactical rear sight.

Table of Contents

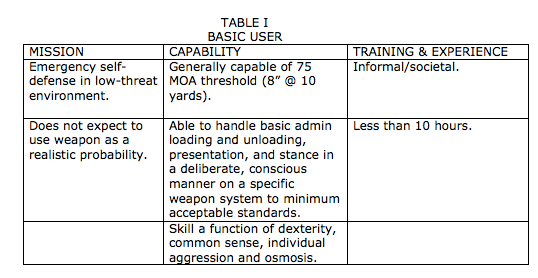

THE BASIC USER

The vast majority of armed users fall into this category. This is the gun-somewhere-in-the closet–or-sock-drawer suburbanite. It may be the recreational shooter who was wandering through the gun show and on a whim took the two-hour CCW permit class and occasionally slips that Raven .25 into his pocket. It might also be portions of the non-frontline military and law enforcement community whose role is to perform routine administrative functions.

The reality is that the individual (or his/her organization) sees armed confrontation as possible, but unlikely. This in turn influences the amount of resources devoted to training, which yields marginal capability with the weapon. These are the individuals who can make the weapon work and hit a simple target at close range on a given day if the stress is kept low and the weather cooperates. Their chances in a fight are largely driven by their individual aggression. Their formal training, if they have any, is probably under ten hours. Their techniques are likely to be influenced by what an action star did on the big screen or how Grandpa did it while plinking, hunting, etc.

None of this makes the individuals in this group bad people or lesser Americans. It does inform how they should be trained and what techniques and equipment may be best suited to them.

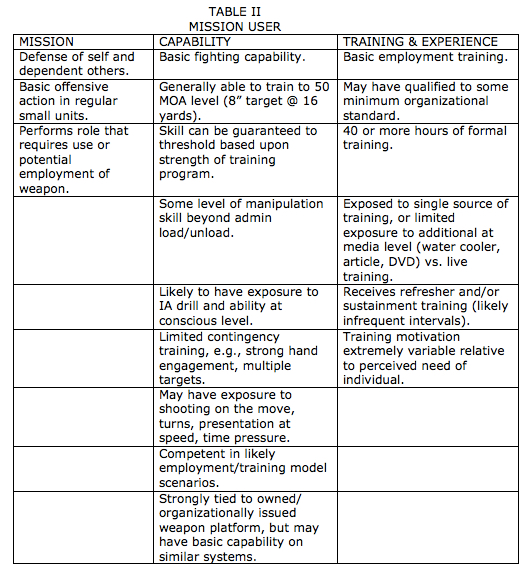

THE MISSION USER

The next large section of the pyramid comprises the mission user group. This is the basic armed professional—military or law enforcement—who in the performance of their duties may be reasonably expected to use deadly force. Because of this, the individuals in this group are trained to a basic standard. They also are likely to have to confirm that standard at some interval via qualifications.

The training program may incorporate some skill progression over time, but it is more common for these guys to essentially remain close skill-wise to whatever level they were initially trained to over the course of their career.

These are the many thousands of men and women who serve and protect us fantastically every day. When placed on the upper end of the reaction cycle, this group does well in most dynamic encounters. However as a group, the gaps in their training show when placed at a reactionary disadvantage or in unforeseen difficulties.

From a mindset perspective, these are professionals who do their job well but are probably neither “gun guys” nor going to think about training much outside of what is asked of them on the job to maintain their expected level of proficiency.

From a threat perspective, this is the basic armed no-good, whether crook or enemy combatant, who has received a basic level of training and is fully okay with shooting you when necessary to accomplish his goal. What he lacks in skill with armed manipulation or accuracy is often offset by an advantage in aggressive mindset that can lead to a reactionary advantage.

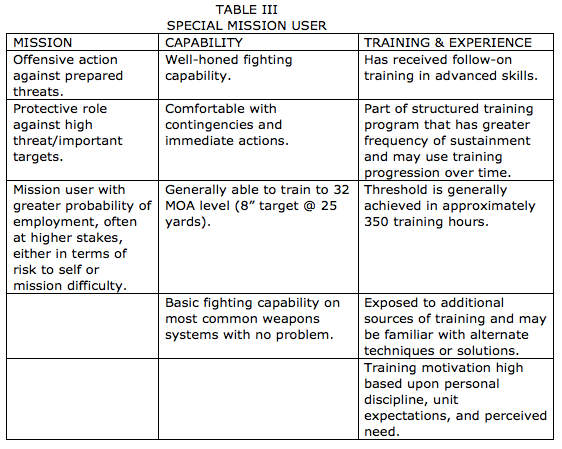

SPECIAL MISSION USER

Think of a big city SWAT team or direct action unit in the military. These are men who know they are going to have to use deadly force and therefore train and behave accordingly. And while they may be disproportionately represented in the circulation of S.W.A.T. Magazine, this is a pretty tiny group among armed users.

Few have the interest, opportunity or resources to put in the required training time to reach this level. In some cases there are dedicated civilian CCW holders who consciously work to get to this level. No one gets here by accident.

From the enemy side of the fence, these are the stone cold killers. This threat understands that he may not be the perfect match for his counterpart user in the accuracy or weapons skill arenas, so will make up for it with superior tactics that allow him to negate distance and marksmanship issues to strike unexpectedly from a flank or cover at close range, possibly with greater firepower.

Time, money, ammo, and ranges. Resources are always limited and each user group must articulate their additional needs based upon mission-linked capabilities.

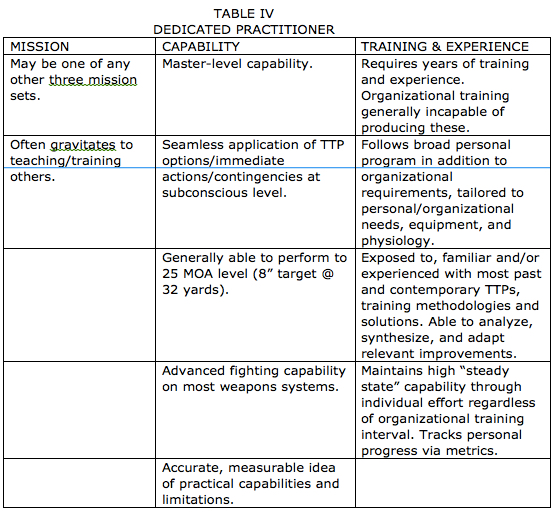

DEDICATED PRACTITIONER

This is the master whom every organization wishes it had. This is the user who combines a passion for training with superior skill and the wisdom gained from hard-won experience and years of effective training. You may know a few—and they are pretty easy to recognize.

He can’t be produced on demand through unit training, because so much of what makes him who he is depends on self-study and personal effort. They are well represented among the top-shelf trainers, some champion competitors and in certain classified units. Like Musashi with his wooden sword, this individual is prepared to win the fight regardless of disadvantage. I have never met someone I would consider at this level who did not have at least 1,500 training hours—most have double that or more.

WHAT SEPARATES THE GROUPS

Training Hours

Some are beginning to challenge the long-held view that shooting is a talent that some are just really good at while others aren’t. There is a direct correlation between the accuracy average differences among the groups and the amount of proper instruction and training they have received. It really isn’t a radical position that the advanced mission user with 350 plus training hours over numerous years can generally shoot well to greater distances than the casual gun owner who shot two boxes of ammo when the pistol was purchased.

The amount and quality of training an organization is willing to commit directly impacts the capabilities of its users. There is also an element of skills progression that affects the capabilities. Some skills have to be built over time as the shooter becomes more comfortable and proficient with manipulations and applying the fundamentals over a wider variety of scenarios.

Another misconception is that 40 hours is ample training for gunfighting. Good fundamental programs tend to run around 40 hours, but that is the foundation that an organization can carefully build upon in manageable blocks. It is not the final solution that an organization sustains with occasional requalification.

Capability

As mentioned in the opening, there is much more differentiating the groups than simple accuracy. A basic user can be counted upon to hit the target the size of a vital zone under moderate stress out to around ten yards, while a mission user can probably do the same stepping laterally and from the holster at speed, and the special mission user can likely match that standard shooting a nonstandard response on the move in low light.

Each group in succession adds more than just additional range to reliably engage threats. Each group brings the ability to counter more potential problems such as stoppages, injury to the shooter, and multiple or moving adversaries to a different degree of certainty.

The organization that ensures its users are trained to special mission levels reduces risk not only to its personnel, but to bystanders as well. Each level ensures that the shooter has more insurance in dealing with contingencies or the need to multitask, engaging dynamic targets under less than ideal conditions.

Mindset

There are big differences in mindset among the user groups. Each has a differing perception of the need for training and the difficulty of the tasks.

The Basic User trains to the best-case scenario, the way that he wishes to have to fight in the unlikely (to them) event that there is an encounter.

Mission Users train to the average fight in their area of operations. This may be driven by the parent organization’s calculation of what the most efficient use of training resources is in preparing for that likely scenario. In some cases that may or may not be “good enough” for what the user actually faces, and the user may not realize the gap until after a challenging situation. The great majority of Mission Users are perfectly happy with the training they receive and some even view it as an acceptable nuisance, since they learned “all they needed to know” at their first formal training.

Special Mission Users train to the worst-case scenario, preparing to reliably handle the most dangerous enemy action in their mission profile. They expect to have to fight using the skills they train to and are prepared for things to go wrong.

The Dedicated Practitioner takes it one step further, training to whatever skill he is weakest in at that time until all skills are as sharp as he can make them. He probably shoots very close to the capabilities of the weapon system and in some cases is pushing the envelope on what is achievable. He follows a broad personal training regimen to build upon the organization’s standard and aggressively tracks his skills progression to ensure that he maintains a high “steady state” of readiness.

THE IDEAL

Studying the accompanying descriptions, it may jump out that the capabilities and training associated with each group would probably be ideal for the group below it. This is the hard reality of resource constraints and organizational priorities. In some small units or departments there is a fortunate coincidence of resources and people who just “get it,” and the training meets the ideal. However, most are forced to accept training compromises that result in users who are one level below what is optimal.

Resource shortfalls are a fact of life in the business. Units that have the time generally lack the money. Those with the funding may have too many shooters but too few instructors and available ranges. And those specialized units that are blessed with great trainers, endless ammunition and state of the art facilities are usually constrained by the amount of time they are able to be off-mission or ready status in order to train.

NOW WHAT?

The four user groups are useful for several things. First is self-identification. Comparing capabilities with training level and mission is always healthy.

The next is the proper framework for evaluating suitability of equipment and techniques for an organization. What works for someone who has years of experience and many hundreds of hours of training may not be the first choice for someone who is armed but essentially untrained. The groups and their differences can be used to properly structure a well-thought-out training progression.

The identification of user groups can be used by special teams to justify the additional resources needed to train properly to the necessary standards based upon the desired capabilities. Too many teams and units have advanced missions but are resourced no differently from Mission Users. Likewise, some Mission Users are trained according to departmental tradition and not according to needed capabilities.

The next time you hear a good tactical or training discussion starting, frame it against the user groups and see it if doesn’t advance the discussion.