I have seen a vast number of different live-fire range designs over the years. Some of these ranges are outstanding for tactical training, while others are nearly worthless.

While Federal agencies normally use already established training sites, many smaller departments tend to use rural land in a relatively informal set up. In addition, when some departments get grants for range improvement, they may be unsure about how to best spend those funds.

The purpose of this article is to offer insight into how departments can save a great amount of money while giving their officers more functional and realistic ranges.

A million-dollar range does not guarantee million-dollar training. Many expensive ranges are simply hollow shells. Some entities build million-dollar ranges and just really don’t have a clue as to what is needed to conduct realistic tactical training for their troops.

Some admin folks who allot where the funds go have a distinctly different view of what a live-fire range needs than a 20-year veteran SWAT team leader does.

Many think of the range as a place to “qualify.” There is a huge difference between “qualifying” and “tactical training.” Qualification generally means static one-directional timed fire. This is a far cry from what officers actually need to increase their operational effectiveness.

Table of Contents

WHAT DO WE NEED?

Some of the most limited and hard-to-work ranges I have been on have been the million-dollar ranges. As soon as I hear the brief from the liaison officer over the phone (before I arrive), I can sense difficulties without even seeing the range.

Sometimes when administrators allot funds for range development, the personnel responsible for accomplishing the mission are not well informed about what is most versatile and beneficial to the needs of the officers who will be utilizing that range for tactical training. Time and time again, I’ve seen money put into a facility only to make it less user friendly than it was before.

If you use your imagination, you can do a lot with very little. I have traveled to many foreign countries and worked with men who had next to nothing in the way of range target systems and logistics. Many of these training evolutions have been among the most memorable and rewarding I’ve ever conducted. These men occasionally seem embarrassed that all they have available for live-fire training is a gravel pit or a clearing in the jungle with three dirt berms. I tell them that what they have is totally sufficient to accomplish our mission of training up their tactical team.

We need to get back to the basics. Let’s talk about targets and what is really needed to facilitate effective training.

Though this range cost taxpayers a lot of money, its actual usefulness for realistic tactical training is severely limited.

WHAT TYPES OF TARGETS?

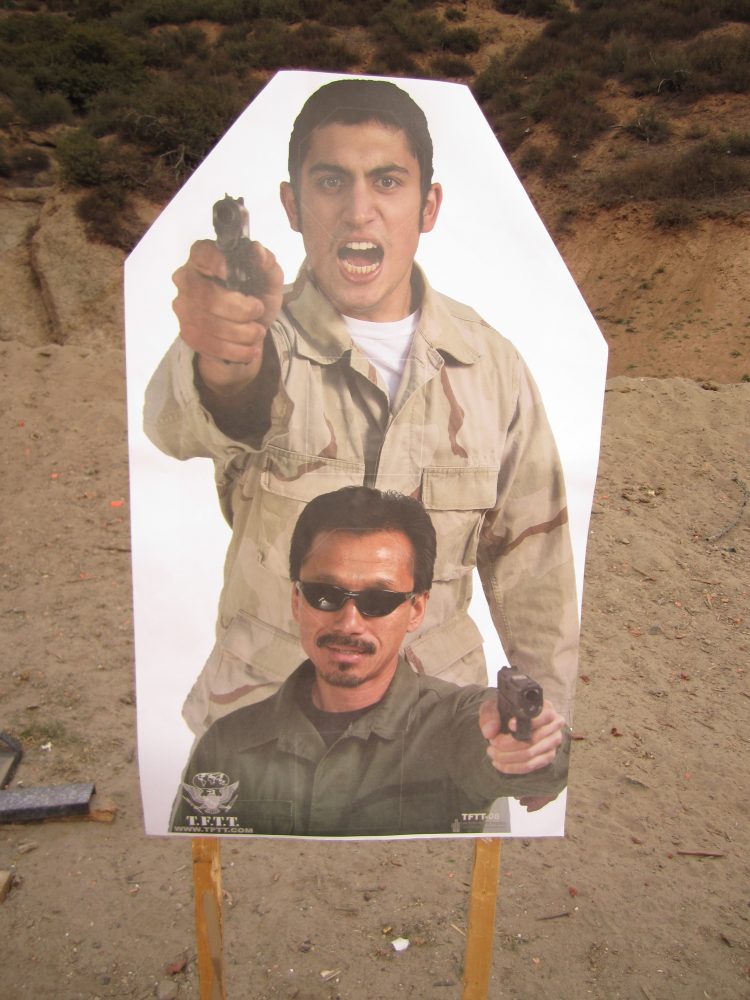

Paper targets should be realistic and offer the shooter good mental imagery of a human adversary, because that’s what they will be fighting. If I were the chief or sheriff of a department who came out to the range to observe live-fire training and found the men shooting at B27 or other generic silhouette targets, I would ask my training sergeant, “Why are you having my officers fire on targets that are not presenting a threat to them?”

Some men who have been training for years on bowling-pin type image targets may one day be shocked to see it’s not a bowling pin that is shooting at them.

Mix of IPSC targets in simple target stands, plus one torso steel per two shooters, is very effective combination.

No shooting on targets that do not have weapons visible. If we are training men to only fire to protect themselves and others from death or grave bodily injury, why are we shooting at blank paper or cardboard targets? I usually ship or fly with my own targets. When that is not possible and the only thing available is blank cardboard, we cut out shapes for pistols to spray paint overlays on the targets, as a matter of common sense.

This simple problem-solving technique dates way back to when I was a young Marine and reading these types of articles in S.W.A.T. Magazine. In fact, when I first started out in this industry, I learned a great deal from reading articles by some of the authors who still write for S.W.A.T. today.

There should be a logical progression of target imagery/scenarios that take the shooter through more and more challenging scenarios and realistic imagery based on their competence level.

It does not make sense to have basic shooters firing on hostage head targets at 15 yards. They are being set up for failure and will quickly become demotivated.

Men should be firing on targets that present a threat.

MOVEABLE TARGET STANDS

Target stands can and have been made out of every conceivable material and configurations. I have seen them constructed from old metal wheels, metal I-beams, plastic buckets full of concrete, and wood. Wood target stands are very economical and easy to replace.

The target stand should be considered semi-permanent equipment. The vertical wooden supporting slats that hold the cardboard target should be considered expendable items. Wooden support slats are superior to steel, as a hit on steel at close quarters will spray jacket fragmentation back on the shooters.

Proper mix of photo and steel targets makes for a good day!

This does not mean I expect students to be hitting the wooden slats during a pistol course that may have a 25-yard qualification, but keep in mind that these same slats are used on shotgun courses and dynamic suppression of enemy fire and break contact drills. Either way, they will be shot.

Tubular steel and angle iron make some of the best paper target stands that I have seen. Target stands should be lightweight and easy to move and stack. You need moveable target stands to conduct multiple angle and directional target engagement.

Ranges that have “pits” that contain the turning targets and offer protection for the pneumatic hoses really limit you when that is the only place the targets can go.

Concrete slabs and turning targets might be great when all you do is static, straight-on fire, but they restrict you greatly when you want to move targets around and engage them from the left and right.

Ability to get vehicles on the range to shoot from and around is important.

STEEL TARGETS

Steel targets are a critically important part of training tactical personnel. The advantage of shooting steel is that it gives instant feedback to the shooter of when he is hitting his target. It is also somewhat reactionary by way of both a visible and sometimes audible signature, which is important for teaching follow through on the target.

I believe the size of the steel target should be challenging, but not excessively so. We are training our officers for combat shooting. Hitting a four-inch plate from 15 yards enters into the bounds of bull’s-eye shooting.

These targets should be the size of the primary stopping zone, which is the head and upper chest/throat region. They are ideally placed at the appropriate height and are static, meaning you do have to reset them each time. I used reactionary drop steel targets for several years, but eventually realized that any labor-intensive reset target means more downtime for students. I strongly dislike any downtime for students.

All steel targets need to be maintained in good condition. Steel that has become warped or pockmarked must be replaced. The seriousness of firing on unserviceable steel cannot be overstated. You are risking not only an injury, but quite possibly a death.

Because I travel extensively, I hear the same story over and over: “Yes, we have steel targets.” What they usually have is a motley crew of mild steel that has either been penetrated by 5.56mm or heavily dented by shotgun slugs. I am telling you that if these men continue to fire on targets in this condition, there will be an injury.

VEHICLE ACCESS, NIGHT SHOOTS AND MORE

Can we pull cars onto the range? Don’t make the mistake of blocking off the range to vehicle access. Being able to effectively and safely access our weapons while inside and exiting our vehicles is an important skill for officers to possess.

I have read on some students’ critiques comments such as, “I have been on this department for 16 years and this is the first time I have fired from my vehicle in training.” There is no excuse for that.

Can we shoot at night? I was once told that we were not able to conduct night training at a certain range because they had not yet installed lights at the facility. They planned to install electricity in the next few months, and we could conduct the training at that time. I replied that I didn’t need lights as I planned to do a night shoot. His response was, “How can you do a night shoot if we don’t have any lights on the range?”

I am serious here—what are these people thinking?

Three-way berms are critical for conducting any realistic drills. We do not operate in a one-directional environment, so why are our ranges set up as such?

I have shown up for courses at a few venues that feature 30-foot berms on each side, with the normal target placement straight ahead. As I begin to set my targets up on the left and right in preparation for the men to execute live-fire room façade entries, I have had one or two “rangemasters” run down and ask, “Why are you putting your targets on the left and right?” My answer is that the men will be shooting to the left and right when they execute this CQB drill.

Then I hear, “You can’t shoot left and right!” Why not? These berms are 30 feet high and 20 feet thick. “Well, we just don’t do that.” Roger that. That is precisely why I am here.

If overpenetration remains a concern to your rangemaster or governing authority, consider using frangible ammunition and/or physically walking the range officer/safety officer through your course of fire to demonstrate how safe the drill actually is. “You don’t know what you don’t know” and you can’t assume the range officer has been trained in dynamic team movement drills.

In conclusion, training budgets are becoming smaller and tighter. If funding is wisely spent on what is really required—as opposed to what some non-operator thinks the men need—the officers will benefit much more and be operationally more effective and safer.

Max F. Joseph is the founder and training director of both Tactical Firearms Training Team (TFTT) and the Direct Action Group. Max has been involved in Special Operations and training nonstop for the last 27 years. He has trained and worked with counterterrorist officers and troops from Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and South America. He also has extensive experience in executive protection and has worked details in Central America, South America, Eastern Europe, and Afghanistan. He can be contacted at www.tftt.com or [email protected].