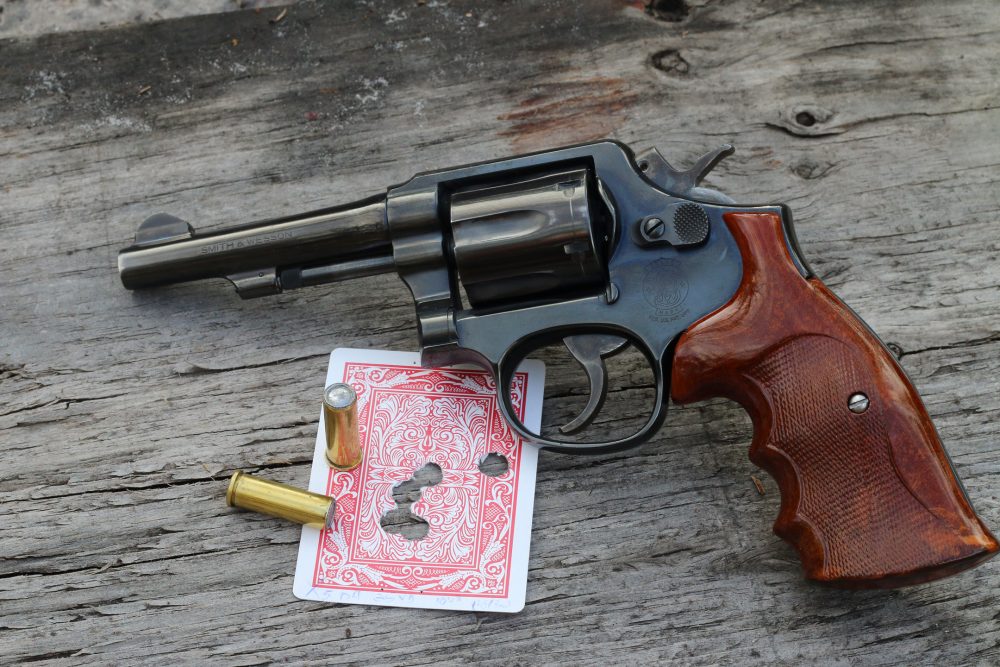

Classic medium-frame revolver still has a place in a shooter’s toolkit and is a great skill builder.

Ah, the wheelgun…

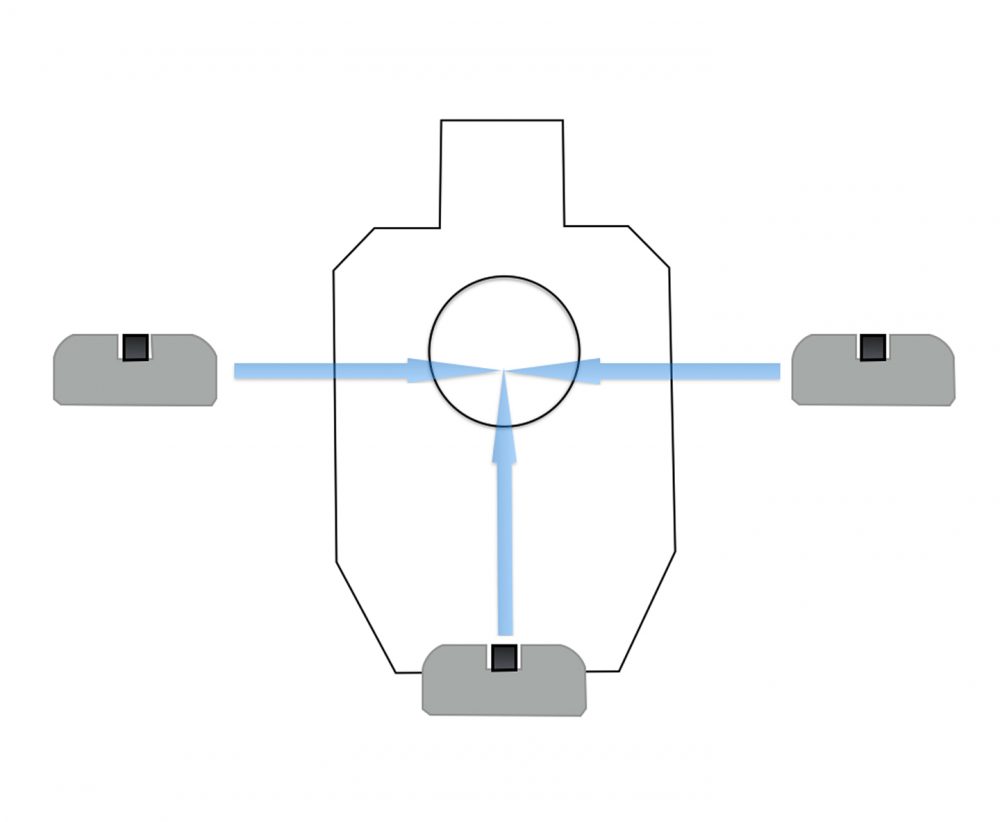

Asking where it fits in an iPhone world draws interesting responses. Many shooters who have come into the community in the last decade view the service revolver as a throwback one-half step ahead of cowboy action shooting. Others view it very specifically as a pocket and/or ankle gun à la the five-shot J-Frame.

Is there a place for the sixgun in the modern world? In a word, yes!

Table of Contents

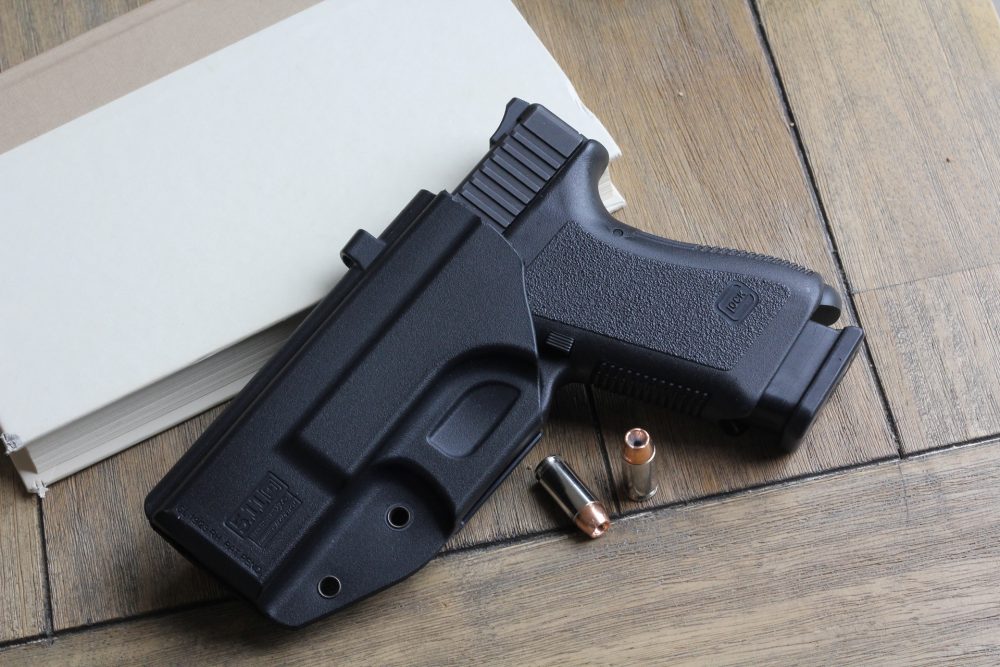

SEMI (SUITABLE) AUTOMATIC

As great a choice as the modern service auto is for most gun owners, it is not necessarily the best choice for everyone. For those whose hackles just shot up—settle down. There are always going to be a group of people (not shooters) interested in having a firearm for self-defense but wholly uninterested in and more than a little intimidated by those same handguns. These are often ideal revolver people.

A buddy of mine was overseas flying Marine helicopters when his wife suddenly changed her stance on having a gun in the house. A late-night drunk banging loudly on the wrong door can have that effect.

I showed her a few choices and gave her pick of the litter. This was a sharp, intelligent lady. She wouldn’t even discuss a long gun. She wasn’t the least bit interested in understanding how a Glock worked, ditto a SIG P239. When I showed her the Colt Cobra, she immediately appropriated it and put it on home guard.

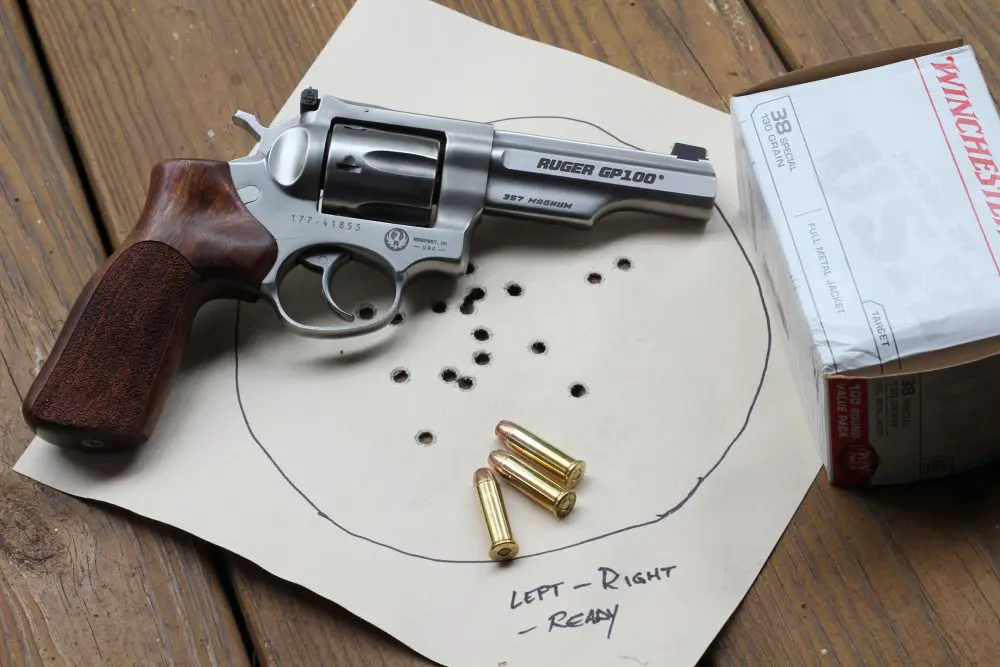

Left, Right, Ready drill has shooter combine movement of the gun with cycling the trigger.

On the other end of the spectrum, I have a family member who is attached to a Glock 23 as a nightstand piece and has shot it maybe twice since Bill Clinton left office. Although comfortable and functional with the operation of a semi-auto, this person is generally uneasy with the pistol in Condition One bedside, even holstered. You may not agree, but that is a pretty common concern for the non-enthusiast/non-professional.

When visiting, I occasionally check the Glock. Over time I have found it Condition One, Condition Three, and vague non-conditions such as partially filled mag halfway inserted, chamber empty and pile of rounds scattered nearby. When queried on the last, the individual admitted to several instances of chambering a round upon “bump in the night” noise, then clearing the chamber and kinda-sorta reinserting the mag as they went back to sleep.

An old-fashioned double-action (DA) revolver that sits ready to go and unfussed with may be preferable to the latest, greatest auto pistol that the human in the loop has rendered less effective by inconsistency of condition and lack of confidence in its safety at ready.

To that end, the nickel Smith & Wesson Military & Police in the photo has been in active use for four generations. Generation one was a town constable in the Deep South and “carried it” on the seat of his car, retrieving it as needed. Generations two through four have had the old Smith as a house gun. It is woefully behind in comparison to almost any pistol you will see in this issue, but is also likely still equal to the task.

Does the revolver have issues? You bet. Night sights are uncommon and hard to retrofit, capacity is modest, and the DA trigger is hard for the average shooter to hit with past egg-toss range.

This .38 S&W M&P has reliably served four generations.

TRIGGER TRAINER

If you see me shooting as opposed to training, chances are very strong that it will be with a revolver. I very much enjoy shooting the wheelgun. To me some of the most relaxing shooting there is comes behind a quality double-action .38 with mid-range loads. However, there are real benefits to actually training on a medium-frame revolver. I am conspicuously “unpicky” when it comes to triggers on my pistols and rifles. I attribute this to many thousand cylinder revolutions of double-action revolver shooting.

On one deployment, I had possession of a captured Model 10 Smith & Wesson with a two-inch barrel, and a gold-plated Colt Detective Special. No ammo, just the guns. I dry fired those two—a lot. I was already proficient with DA triggers, but the extended time clickety-clicking those .38s to relieve boredom or stress made a big difference in my overall trigger control across all platforms.

When you’ve gotten to the point where you can smoothly cycle a DA trigger strong or weak hand, a two-stage creepy AR trigger is suddenly much more manageable. Quality time on the “trigger-cocking” wheelgun can help a shooter find a whole new level of capability with all firearms.

Still skeptical? If ten readers acquire a decent revolver and make a short pile of brass with the following drills, nine will write in and thank me. And the tenth? Well, there’s no helping that sourpuss.

Fifteen-yard steel used in Rolling Out drill with this Model 15.

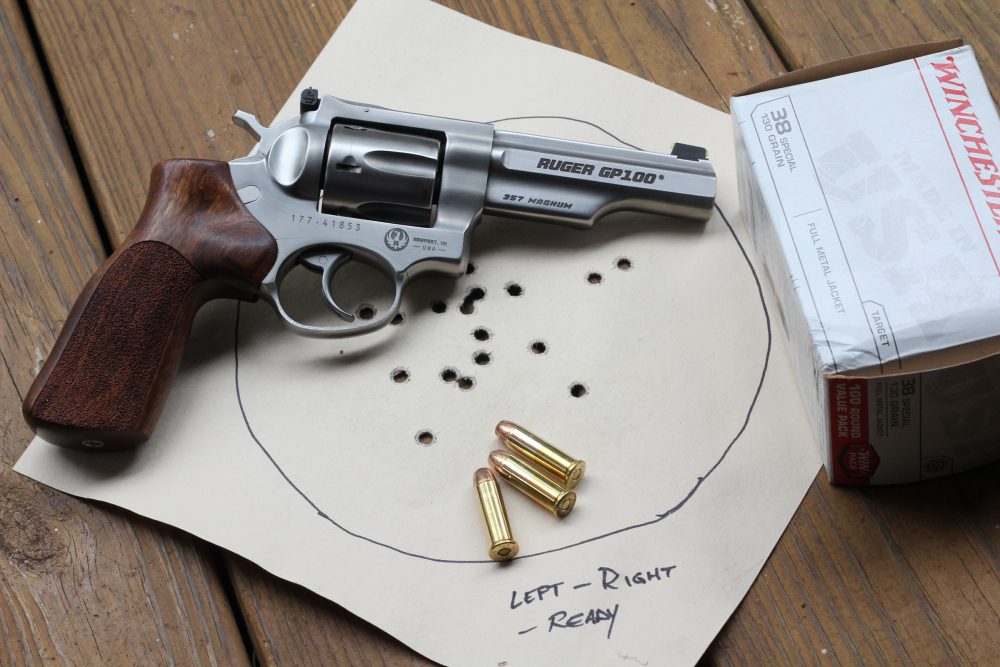

DRILL 1: LEFT, RIGHT, READY

The goal of this drill is simply to learn the stroke of the double action and combine it with movement. The shooter sets up an IDPA-type silhouette or a plain eight-inch circle at a convenient distance. Five to seven yards is a decent starting point.

The aspiring revolver-ero begins holding the wheelie at full extension aimed generally about 18 inches off the left edge of the target. When ready, he starts moving the gun toward the circle as he begins to roll the trigger backwards. Ideally the trigger moves smoothly to the rear at an even pace and the shooter controls the speed of the lateral movement so the shot breaks at some point inside the eight-inch circle.

I am perfectly happy for the shot to break right as the gun crosses the edge of the circle.

Timing and coordination are more important here than trying to cut a rathole in the center inch of the circle. As the left-to-right movement begins to shape up, switch over to—you guessed it—18 inches off of the right side. Now the shooter repeats moving from right to left.

Medium-frame revolver remains a solid choice for many non-enthusiasts who want a home-defense gun.

When that is solid (typically slightly more difficult for the right handed), the shooter shifts to a low-ready stance 18 inches below the six o’clock edge of the circle. Some shooters find the raising motion more difficult to smoothly cycle the trigger, while others pick up a lot of speed and tempo here and are quickly “rolling” shots into the circle from below.

This is not a tactical drill. It is simply a mechanism to demystify the heavy trigger and help combine the manipulation of the trigger with movement of the revolver. When a shooter can do this well, the DA pull is no longer intimidating and the tendency to snatch the trigger all the way from the hamstrings decreases.

This drill translates very well to semi-autos with triggers that have take-up or weighted pre-travel before the “wall” or break. There the shooter executes similarly, with the goal to get through the take-up on the movement and break through the wall just as the front sight crosses the circle’s edge.

Some gun owners are not ideal semi-auto people. This pistol is in a non-standard state of “readiness” due to its owner’s inattentiveness: mag not topped off nor fully inserted, chamber empty as found.

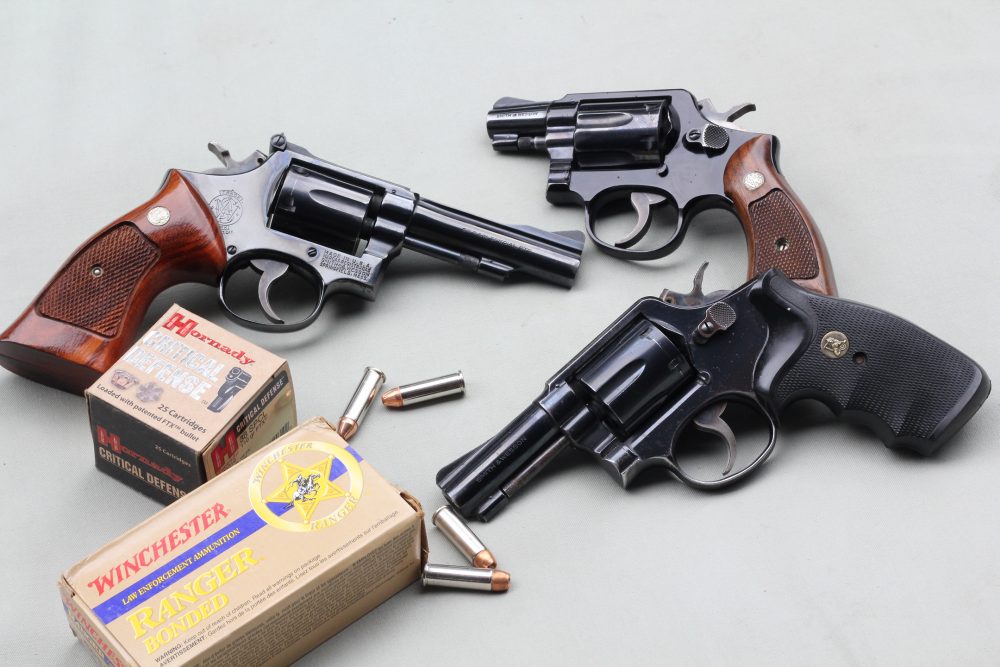

DRILL 2: ROLLING OUT

This drill is best conducted on a steel plate, but an eight-inch paper circle will work. The setup is ten yards with a goal to earn some extra yardage as skill improves.

The shooter begins with the sixgun at the ready, muzzle downrange wherever his hands join in his drawstroke. On the buzzer, the shooter begins pushing the gun out toward the steel. The objects are to get pressure on the trigger as soon as the front sight is visible, and get it rolling to the rear as the front sight settles into the rear notch.

The shot should break as or shortly after the sights get deep into steel. Two seconds is a good starting marker for time to ensure there is no halting, staging or getting all the way out and then powering through the entire trigger weight. If the trigger is exceptionally heavy or the sights or lighting poor, 2.5 seconds may be excusable.

Quality of the sights and trigger will affect the time it takes, but most of the time is spent getting a bunch of muscles, joints, and senses to coordinate. As an example, I was running this drill with a vintage Model 15 that had a pretty standard trigger in times that ran from .94 second on the low end to 1.25 on the slow end from 15 yards using Black Hills wadcutters.

Swapping over to a circa 1920s Colt Army Special with a smooth but heavier trigger that stacks the weight differently as it cycles and sports tiny period sights bumped the time up nearly 1/4 second. The Colt clanged steel reliably in a bracket from 1.2 to 1.4 seconds.

This drill is also an excellent learning drill on a J-Frame snubbie. If the shooter isn’t making it happen with the Airweight’s tiny grips and sights on an eight-inch paper target at seven yards, increasing the ten-yard steel size to the foot-long center of a Pepper Popper may be more useful.

Over time, the snubman can absolutely run the drill as originally laid out. I ran it with the same 15 yards/eight inches as above with a 1960s vintage Colt Detective Special with no issues, at nearly the same bracket as the K-Frame Smith.

Garden-variety $300 pawnshop Model 10 has excellent trigger and accuracy, as this 25-yard group shows.

I CAN DO THAT?

The real magic in a medium-frame revolver for many Glockenshooters is in the typical accuracy and “wait-a-minute” single-action trigger.

In working one on one with a few hardcore operational shooters over the past year, I’ve had a similar scenario play out. Training is winding down, we’re in the “cooldown” phase, and I break out the wheelgun.

In several cases, the shooter had never really fired a revolver. They pick it up and immediately shoot a slow or timed fire group that rivals or exceeds their personal best on the service auto. Huge confidence booster!

The double-action revolver tends to come with a single-action (SA) break that leaves no excuses. Measuring across a dozen or so second-hand K-Frames, the average SA weight was 3.3 pounds and every single gun had the kind of break you pay a quality gunsmith to achieve in a 1911.

Coupled with the typical “inch and a half-ish” accuracy with good ammo that a revolver brings, a shooter can do great accuracy work at 25 yards to build skills. Once a shooter has easily held the bull with the .38, he tends to more easily tackle accuracy training with the auto.

My personal standby accuracy drill is the Tuf n Ruf (TRAINING WITH A CLASSIC, July 2015 S.W.A.T.). The shooter has five timed-fire shots in 20 seconds and five more shots in a ten-second rapid-fire string at 25 yards for a 100-point possible. With a wheelgun, I habitually shoot the timed fire single-action to see what I can do. The results usually rival my best 1911 runs and exceed my Glock/M&P runs. For the rapid fire, I roll all five shots double-action.

Wheelgun remains a great ankle gun, like this Ritchie Leather Co. ankle holster and Colt Cobra.

Running a DA trigger on a 25-yard bullseye is strong medicine. It is humbling at first, but a shooter’s will to excel kicks in and takes over. That’s when real learning occurs.

Both the earlier drills allow a fairly coarse level of sight alignment, where 25 yards requires the shooter to rotate the cylinder and drop the hammer while keeping the sights as they should be. I’m not aware of anything that better teaches a shooter the connection between sight alignment and trigger control than to shoot from 25 yards double-action.

There you have it. I’ve done my best to convince you to pick up a revolver. When you’ve made a drag line on the cylinder from dry fire and running these drills, your trigger finger will be stronger and you will likely be a better shooter.

And I suspect you may find out you actually enjoy the wheelgun too!

Ethan Johns is a military professional with worldwide experience in specialized units. He has taught and been responsible for numerous advanced skills and weapons courses within multiple organizations.